Hammam al-Shifâ’

(736/1336)

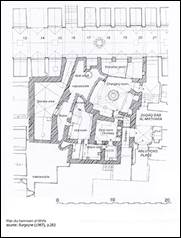

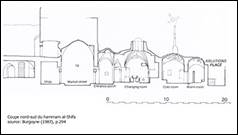

Localisation : au sud de l’allée couverte du sûq al-Qattanîn (D4.6).

Réf :

Burgoyne (1987), n°24c

Meinecke (1992), 9C/336

Historique

Le hammam est élevé pendant la grande campagne de réaménagement du quartier par le gouverneur de Damas Sayf al-Dîn Tankiz de 736/1335-1336 à 737/1336-1337 avec la construction du sûq al-Qattanîn (736/1336), du khân Tankîz (736/1336) et du hammam al-‘Aîn déjà construit depuis 728/1328. Le bain est construit en liaison avec cette allée marchande couverte dont l’accès se fait via les baies 18 à 20 du site. C’est peut-être la dernière construction de cette campagne, ce qui expliquerait son plan plutôt irrégulier.

On doit aussi à Tankiz la madrasa Tankizîya (728/1328) et de nombreuses autres constructions sur tout le territoire, notamment à Damas avec la madrasa Tankizîya (739/1338), le tombeau Kaukaba’îya (730/1330) et la mosquée/tombeau al-Tankîz (718/1318) où il est inhumé.[1]

Sa madrasa de Jérusalem conserve un acte de donation (waqf) qui mentionne ce hammam comme le hammam sud :

[The

waqf includes] all the cells

belonging to both adjacent

ḥammāms, the southern

and the western that were established by the above referred endower [Tankiz], let God glorify his supporters, they are standing in Wādī

al-Ṭawāḥīn in Jerusalem.

The southern one [i. e.ḥammām]

[…] is closed by a private door leading

to a changing room, around which are platforms constructed

of stone and lime; and in it is

a cold water pool, paved-it

and the floor of the mentioned

mashlah [changing

room]- with colored marble. On the west of this mashlah is

a rawshan one ascends

to it by a stair of stone;

and on its east, there are three iron windows with

shutters that overlook the garden which has trees of citrus and

roses. This garden is added to this ḥammām

as part of its rights. And

one enters from this mashlah to the

interior of this bath. It contains a dome that is vaulted

[maʿqūda] with

cups of glass [jāmāt.

pl.

/ jām.sing.; Persian “cup”]; below which [the dome] are four marble basins; and

four compartments [maqāṣīr]

vaulted by domes with cups and of them [the compartments] three are covered with colored

marble; each one of them encompasses two marble basins; and the fourth one encompasses one marble basin; and in the glass chamber

[the main hot room?] of this bath is

a marble basin and a marbled

washtub [ṭashtiyya]

supplied with cold water;

and

the floor of the entirety

of this mentioned ḥammām and its compartments are marbled with colored marble;

and attached to this

ḥammām is

his blessed iqmīm [furnace] that consists also of water equipment [Āla] and in it [the iqmīm] a maṣnaʿ

[installation] that runs its water; and the water is

divided between this ḥammām and the ḥammām whose mention is coming, that

is the western of the two mentioned ḥammāms and is the smaller of the two, and the entirety of the interior of this ḥammām and its floor is marbled

with colored marble; and in the iqmīn

[same as iqmīm,

that is furnace]

that was previously mentioned is the equipment of this ḥammām also, which is

dedicated for its running

water and its basins [wa-qidrāhu];

and these two ḥammāms have the rights

to water from the canal known

as al-ʿArrūb, and it

is a confirmed right. Both ḥammāms are bordered from the south by al-Ṭahāra that was

established by the donor [Tankiz] let God bless him, and from the east by ḥakūrat al-Ṭahāra

[garden] and to the north

the road leading to the Ḥaram

al-Sharīf from a gate known as Bāb

al-Siqāya (i.e. the gate

of getting water/bringing

water); and in it [to the road leading

to the Ḥaram] opens the gate

of the, previously mentioned,

western ḥammām; and to the west [of the two baths] is the road leading from Wādī al-Ṭawāḥīn to the pool that receives the water

from Qanāt al-ʿArrūb;

And in it [i.e. the road of Wādī

al-Ṭawāḥīn] the gate of the big ḥammām

is open.[2]

Epigraphie

Pas

d’inscription.

Biblio complémentaire

Dow (1996), p.87-90

Kenney (2009),

p.109-114

Daadli/Barbé (2017), p.66-93

Documents anciens