Qal’at Subaiba/Nimrod (n.d.)

Localisation : aux pieds du mont Hermon/Jabal al-Shaykh, par l’actuelle route 99, à 6km à l’ouest de Majdal al-Shams.

Réf :

Conder/Kitchener (1881), p.125-128 (plan et gravure de la

tour T07)

Deschamps (1939), 146-174

Ellenblum (1989), p.103-112

Graboïs (1970), p.43-62

Guérin (1880), II, p.324-327

Meinecke (1992), 4/23

Porter (1889), p.132-136

Robinson/Smith (1856), p.402-404

Wilson (1881), II, p.119-120

Amitai (1989), p.113-119

Amitai (2001), p.109-123

Berchem (1888), p.440-470

Ducène (2025), p.105

Hartal (2001), p.54-55

RCEA 4737

Sharon (1999), p.77-87

TEI, n°2379, 2462, 2622, 4157, 28285, 28286, 28287,

28288, 28289, 33255, 33257, 33813

Historique

Périodes antérieures

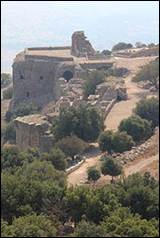

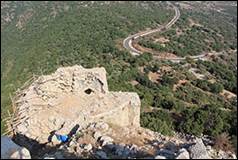

La forteresse est située sur la route qui relie les villes du littoral de Acre, Tyr et Sidon à Damas elle repose sur un étroit éperon rocheux à l’extrémité est du Mont Hermon/Jabal al-Shaykh, à 820m d’altitude.

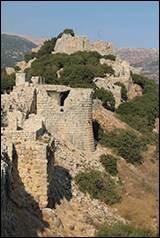

Le terme actuel de Qal’at Nimrod est une appelation des Druzes à la fin du 19e siècle, la forteresse est parfois citée, à tort, comme château de Banias.[1] Le plan de la forteresse suit le relief très accidenté du site entouré de profondes vallées surtout au nord, il s’étend sur 450m de long et de 60m à 160m dans sa plus grande largeur.

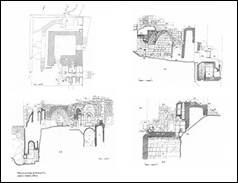

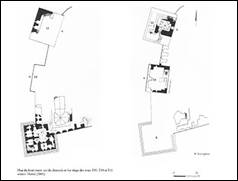

Le site se divise en trois parties : une citadelle à l’extrémité orientale juchée sur un monticule, un grand terrain ouvert entouré d’un mur et l’ensemble ouest comprennant les deux tours massives nord-ouest et sud-ouest (T11 et T09).

Le site est occupé par les Croisés en 1129-1132 et 1139-1164, ils ont peut être élévé un édifice.[2] La forteresse est, principalement, l’œuvre de l’Ayyûbide al-‘Azîz ‘Uthman qui commence la construction vers 625/1227 et l’agrandie en 627/1230.[3] La dernière campagne est celle du sultan Baybars (r.17 dhu’l-qa’da 658/24.X.1260 – 27 muharram 676/30.VI.1277).

Période Ayyûbide

Al-‘Azîz, pour le compte du sultan al-Mu’azzam ‘Isa (r.615/1218-624/1227), fait d’abord construire la citadelle sur le monticule est (T17-T21) avec son réservoir, ses propres murs et le fossé puis la partie basse avec son mur d’enceinte, une inscription permet de dater le début des travaux en 625/1227 (inscription n°4 sur plan, ill.1). A partir de 627/1230, il agrandit la forteresse vers l’ouest avec l’élévation du front ouest et des deux tours nord-ouest et sud-ouest. Les inscriptions retrouvées sous les murs, toutes datées de cette année, permettent de suivre l’évolution des travaux (inscriptions n°6-10) qui donnent ainsi à la forteresse sa forme actuelle.[4]

Une inscription mentionne une phase de travaux ou de finition en 637/1239 attribuée à Fakhr al-Dîn Hasan (inscription n°10 sur plan, ill.1).

Période Mamluk

Au printemps 658/1260, la forteresse subit l’assaut des l’armées de Kitbugha, néanmoins les dégâts occasionés par la conquête apparaissent exagérés. A la suite, le dernier gouverneur ayyûbide de la citadelle al-Sa’îd Hasan ibn al-‘Uthman, est exécuté sur l’ordre du sultan al-Muzaffar Qutuz (r.24 dhu’l-qa’da 657/12.XI.1259 – 15 dhu’l-qa’da 658/22.X.1260) suite à sa collaboration avec l’armée Mongole.

Le sultan Baybars (r.17 dhu’l-qa’da 658/24.X.1260 – 27 muharram 676/30.VI.1277) donne la forteresse, Banias et ses environs à son émir Badr al-Dîn Bilîk al-Khazindâr al-Zâhirî. La forteresse perd ainsi son rôle de forteresse frontière qu’elle avait précédemment, toutefois elle reçoit beaucoup d’attention grâce au rang très élévé de son nouvel occupant, car Bilîk est aussi le vice-roi du sultan (na’îb al-sultana). Ce territoire sera géré par Bilîk de manière quasi-autonome et avec la confiance du sultan jusqu’à sa mort en rabi’I 676/Août 1277.

Baybars visite le site en 667/1268, il est possible qu’il donne alors des consignes pour rénover la forteresse, ces travaux sont mis en œuvre par Bilîk sous le contrôle de son émir Baktût al-Khazindâr, qui est nommé gouverneur de la forteresse. Cette campagne semble s’achever en 674/1275, date mentionnée sur les inscriptions de restaurations (inscriptions n°11-15 sur plan, ill.1).

Les travaux concernent surtout les fronts sud et ouest :

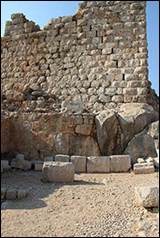

Le front sud est équipé de quatre tours circulaires (T02, T05, T07, T16) qui sont insérées entre les tours quadrangulaires déjà existantes afin de renforcer les faiblesse du mur d’enceinte. Ces tours ont un diamètre de 10 à 18m, une base pleine, un parement à bossages, un seul étage et un toit plat servant de plateforme de tir, les salles intérieures présentent un plan hexagonal ou pentagonal. Chaque tour est connectée au mur d’enceinte par une galerie d’archères.

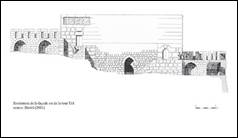

Le front ouest est renforcé par deux tours quadrangulaires (T09, T11) enchassant les anciennes tours ayyûbides.

Une inscription non datée fait état de travaux de rénovation de corbeilles soutenant les machicoulis (kibâsh), cette inscription a été découverte dans la cour ouest de la tour T09 avec une sculpture de félin (lion ou panthère), symbole du sultan al-Zâhir Baybars[5] ; on retrouve ces emblèmes sur Bâb al-‘Asbât porte du front est de l’enceinte de Jérusalem, au Jisr Jindas à Lod, sur la tour T43 du Crac des Chevaliers et à sur la tour T04 du château de Kerak.

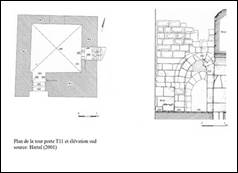

La tour nord (T11) dite tour de Bilîk s’élève sur trois niveaux, elle possède son propre réservoir et un passage secret menant au front nord. Cette tour fait office de résidence fortifiée, avec une vue dégagée sur la ville de Banias et son territoire. Elle présente aussi certaines innovations architecturales. L’aménagement intérieur est pensé pour rendre la vie quotidienne plus confortable ; ainsi les latrines sont isolées dans les angles de la tour et connectées à un système d’évacuation des eaux usées et les larges galeries servent de lieu de vie et d’habitation pour la garnison.

Les parties fortifées du site sont donc assez bien connue, mais bien que le site soit bien préservé, il y a peu d’informations sur les bâtiments internes tels que les entrepôts, magasins, cuisine ou communs. Au sud-est de la forteresse on trouve un réservoir et un cimetière.[6]

L’histoire de la forteresse après cette période est lacunaire, on sait seulement que des gouverneurs continuent à être nommés par les sultans successifs et qu’au 15e siècle, le site abrite une prison pour les émirs tombés en disgrâce.

Le site a été endommagé par les séismes du 30 octobre et du 25 novembre 1759[7], notamment les tours T09 et T11, et du 1e janvier 1837. Malgré cela les voyageurs explorant le site au 19e siècle, leurs gravures puis les photos au début du 20e siècle, se plaisent à admirer la puissance de cette forteresse perchée sur son éperon rocheux (voir plus bas).

Epigraphie

Tableau de concordances des inscriptions de Subaiba.

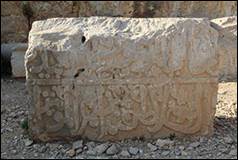

625/1227-1228. Texte de construction 4 lignes (35x120), trouvé à l’ouest de la tour T01 (inscription n°4 sur plan, ill.1).[8]

« Basmallâh. Has ordered

the establishment of this blessed barbican our lord the sultan al-Malik

al-‘Azîz ‘Imad al-Dîn, the sword of Islam, the crown of the kings, the sun of

the sultans, Abû al-Fath ‘Uthmân ibn al-Malik al-‘Adîl, helper of the Commander

of the Faithfull, seeking the nearness of Allâh, may He be exalted, in the year

625 (1227-1228) ».

627/1230. Texte de construction fragmentaire 4 lignes (67x87), trouvé entre tour T02 et T03 (inscription n°5 sur plan, ill.1).[9]

« [Basmallâh. Has

ordered the building of this] divinely protected [frontier fortress] the

sinning, erring servant, the needy (for his God’s mercy, al-Malik al-‘Azîz

‘Uthmân, son of our lord, the sultan) al-Malik al-‘Adîl, the scholar, the

scholar ( ?), the doer of good deeds, [the warrior in the Holy War, the

fighter on the border, the raider, the martyr, Abû Bakr ibn Ayyûb, may Allâh

shelter him] with His grace (mercy). The beginning (of the building) of this

divinely protected border fortress was in (the month of ? the year 627

(1230). Its building was supervised by the servant), the needy (for Allâh’s

mercy), Abû Bakr ibn Nasrallâh ibn Abû Suraqâh [al-Hamadhanî (or Hamadânî)

al-‘Azizî] ».

627/1230. Texte de construction 5 lignes (90x80), trouvé en contrebas de la tour T06 (inscription n°6 sur plan, ill.1).[10]

« Basmallâh. [Has

ordered the building of this divinely protected frontier fortress, the

sinning], erring servant, the needy for his God’s mercy, [al-Malik al-‘Azîz

‘Uthmân, son of our lord, the sultan], al-Malik al-‘Adîl, the scholar, [the

doer of good deeds, the warrior in the Holy War, the fighter on the border, the

raider, the martyr, Abû Bakr ibn] Ayyûb, may Allâh shelter him [with His mercy.

The begining (of the building) of this divinely protected border fortress was

in the month of the year 627] (1230). [Its building was supervised by the

servant, the needy (for Allâh mercy), Abû Bakr ibn Nasrallâh ibn Abû

al-Hamadhanî or Hamadanî al-‘Azizî] ».

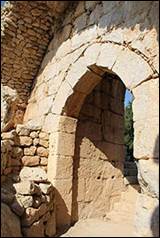

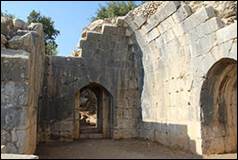

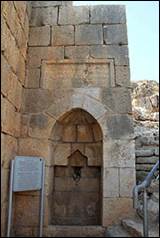

627/1230. Texte de construction 5 lignes (120x90) sur l’arche de la porte de la tour T11 (inscription n°7 sur plan, ill.1, 43).[11]

« Basmallâh. Has ordered

the building of this divinely protected frontier fortress, the sinning, erring

servant, the needy for his lord’s mercy, ‘Uthmân, the son of our lord, the

great sultan, al-Malik al-‘Adîl, the scholar, the doer of the good deeds, the

warrior of the Holy War, the fighter on the border, the raider, the martyr, Abû

Bakr ibn Ayyûb, may Allâh shelter him in His mercy. The beginning (of the

building) of this felicitous tower was in the month of rabi’I, the year 627

(janvier-fevrier 1230). Its building was supervised by the servant, the needy

(for Allâh mercy), Abû Bakr ibn Nasrallâh ibn Abû al-Hamadhanî or Hamadanî

al-‘Azizî) ».

627/1230. Texte de construction 5 lignes (76x140) sur le mur ouest de la tour T10 (inscription n°8 sur plan, ill.1).[12]

« Basmallâh. Has ordered

the building of this divinely protected frontier fortress, the sinning, erring

servant, the needyfor his Lord’s mercy, ‘Uthmân, the son of our lord, the great

sultan, al-Malik al-‘Adîl, the worshiper, the doer of the good deeds, the

warrior in the Holy War, the fighter on the border, the raider, the martyr, Abû

Bakr ibn Ayyûb, may Allâh shelter him in His mercy, and havemercy on us when we

reach his fate. The beginning (of the building) of this felicitous tower was in

the first ten days of the month of rabi’II the year 627 (17-26.II.1230). its

building was supervised by the servant, the needy (for Allâh mercy), Abû Bakr

ibn Nasrallâh ibn Suraqa al-Hamadhanî al-‘Azizî) ».

627/1230. Texte de construction 4 lignes (60x120), trouvé en contrebas de la tour T09 (inscription n°9 sur plan, ill.1).[13]

« Basmallâh. [Has

ordered the building of this] divinely protected frontier fortress, the

sinning, erring servant, [the needy of] his lord’s mercy, al-Malik

al-‘Azîz ‘Uthmân, the son of our lord, the great [sultan], al-Malik al-‘Adîl,

the scholar, [the doer of the good deeds, the warrior in the Holy War, the

raider, the martyr, Abû Bakr ibn Ayyûb, may Allâh shelter him with His grace

(mercy). The beginning (of the building) of the divinely protected border

fortress was in the month of xxx in the year

627 (1230). Its building was supervised by the servant, the needy (for

Allâh’s mercy), Abû Bakr ibn Nasrallâh ibn Suraqa al-Hamadhanî or al-Hamadanî

al-‘Azizî] ».

637/1239-1240. Texte de construction 5 lignes (67x150) sur le mur mitoyen du réservoir SW (inscription n°10 sur plan, ill.1, 70).[14]

« Basmallâh. This

blessed place was renovated in the days of our lord, the sultan, the scholar,

the just, the fighter in the Holy War, the confirmed (by Allâh), the

victorious, al-Malik al-Sa’îd Fakhr al-Dîn Hasan, the son of our lord, the

sultan, al-Malik al-‘Azîz ‘Imad al-Dîn ‘Uthmân ibn al-Malik al-‘Adîl Abû Bakr

ibn Ayyûb, under the supervision of the great amir ‘Azîz al-Dawla Rayhân

al’Azizî, and during the governorship of the amir Mubariz al-Dîn Khutluth

al-‘Azizî in the month of the year 637 (1239-1240) ».

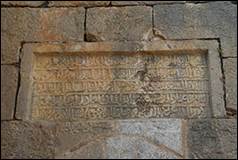

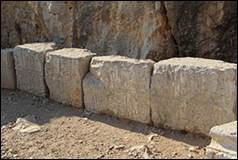

674/1275. Texte de construction 4 lignes en 5 blocs (600x135), aujourd’hui déposée aux pieds de la tour T11 (inscription n°11 sur plan, ill.1, 81-85).[15]

« Basmallâh. This

blessed tower has been renovated through the benefaction of our lord the

sultan, al-Malik al-Zâhir, the most majestic master, the scholar, the just, the

fighter of the holy war, the warrior at the border posts, the heavenly

confirmed, the victorious, Rukn al-dunya wa’l-dîn, sultan of Islam and the

Muslims, killer of the rebellious deviators, restorer of justice in the world,

Abû al-Fath Baybars al-Sâlihî, who shares authority with the Commander of the

Faithful. Ordered its making, our lord, the honorable master, the grand master,

the great commander (al-amirî al-kabirî), the Mamluk of al(Zâhir and

al-Sa’ad, the most glorious, the most felicitous, the exulted, the well-served

(al-makhdûmî), al-Badrî Badr al-dunya wa’l-dîn, the glory of Islam and

the Muslims, the leader of the armies of the monotheists, the king of the

commanders in the world, Bilîk, the (Mamluk of) al-Malîk al-Zâhir and

(al-Malik) al-Sa’îd, may God perpetuate his life (adâma allah ayyâmahu).

This was during the governorship (bi-tawallî) of the great commander (al-amîr

al-kabirî) Badr al-Dîn Baktût [and] under the command (bi-wilâyah)

of the great commander ‘Alam al-Dîn Sanjâr, the great fighter in the holy war,

and the supervision of the master builder, the architect ‘Abd al-Rahman, and

the approval of the master builder (al-mi’mar) ‘Abd al-Wahhâb. (This

was) on the 20 [22 ?] of muharram of the year 674 (18.VIII.1275). (The

inscription was) the design of Yûsuf ».

674/1275. Fragment de texte de construction 3 lignes (50x20), trouvé dans la tour T15 (inscription n°12 sur plan, ill.1).[16]

674/1275. Fragment de texte de construction 2 lignes (110x70) trouvé au SW de la tour T09, aujourd’hui déposée aux pieds de la tour T10 (inscription n°13 sur plan, ill.1, 80).[17]

« [Basmallâh. From what

has ordered its making the honourable master] the lofty, the lord, the grand

ru[ler, the great amîr … the support of the kings and] the sultans, the right

arm of the Commander of the Faithful, [May Allâh perpetuate his life] ».

674/1275. Texte de contruction en 6 fragments (70x90m, 54x115, 54x80, 54x140, 54x80, 54x66) trouvé dans le fossé vers la tour ronde T16 et aujourd’hui déposé vers la tour T10 (inscription n°14 sur plan, ill.1).[18]

« [Has ordered] the

construction of this [felicitous tower our lord the sultan, al-Malik al-Zâhir,

the scholar, the just], the fighter at the frontier posts, the divinely

confirmed, the victorious, [the pillar of the world and of the religion], the sultan

of Islam [and the Muslims], the vanquisher of the deviat[ors and rebels … Abû

al-Fath Baybars al-Sâlihî… ] ».

ca.674/1275. Texte de construction en 4 fragments (72x71, 105x72, 92x72, 67x72) trouvé dans la cour de la tour T09 avec une sculpture de félin (ill.75), aujourd’hui aux pieds de la tour T10 (inscription n°15 sur plan, ill.1, 76-79).[19]

« Basmallâh. Ordered the

work on this tower and its renewal, and [the rebuilding ?] of the blessed

corbels… of the Muslims, noble among the officers of the entire world,

commander of the armies of the jihâd fighters, guardians of the frontiers of

the monotheists, stalwart (?) of the community, succor (?) of Islam,

administrator of the provinces… ».

Biblio complémentaire

Amitai-Preiss (1997),

p.3-5

Pringle (1993), p.108

Pringle (1997), p.30

Sharon (1997)

Sharon (1999), p.57-87

Amitai (2001),

p.109-123

Hartal (2001)

Dotti (2007), n°12

al-Halabi (2006)

Yovitchitch (2007),

p.543-557

Raphael (2010), p.134-146

Hinzen (2016), p.751-764

Margalit (2018), p.1-12

Badichi/Bron (2022)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

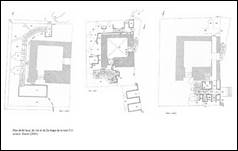

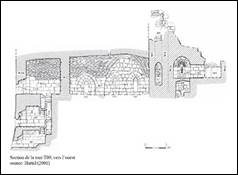

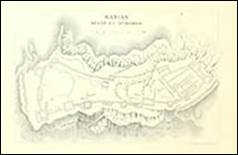

1/ plan général avec localisation des inscriptions |

2/ plan des différentes phases de construction |

3/ vue générale du site |

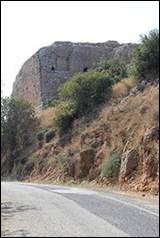

4/ vue du site depuis la route d’accès |

5/ vue du site depuis la route d’accès |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

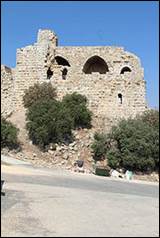

6/ vue du front sud-est depuis la route |

7/ front sud-est avec les tours T01 et T16 |

8/ partie droite du front sud-est avec la tour T16 |

9/ partie centrale du front sud-est |

10/ partie gauche du front sud-est avec la tour T01 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11/ front sud depuis la route |

12/ une partie du front sud |

13/ front sud avec la tour sud-ouest T09 |

14/ front sud avec la tour T07 |

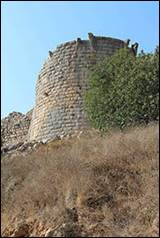

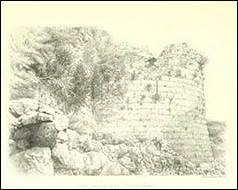

15/ tour T07 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16/ couronnement de la tour T07 |

17/ maçonnerie de la tour T07 |

18/ tour T07 avec le raccord au mur d’enceinte |

19/ tour T08 depuis la route d’accès |

20/ vue est de la tour sud-ouest T09 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

21/ tour T09 face sud |

22/ archères de la face sud de la tour T09 |

23/ tour T09 depuis le sud-ouest |

24/ plan de la tour T09 |

25/ tour T09 face ouest |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

26/ tour T09 face ouest |

27/ tour T09 et T10 |

28/ front ouest avec T09 |

29/ tour T09 depuis le nord |

30/ vestiges de la tour T10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

31/ front ouest depuis tour T09 |

32/ front ouest avec tour T11 |

33/ tour T11 depuis le sud |

34/ tour T11 |

35/ tour T11 depuis l’ouest |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

36/ plan de la tour T11 |

37/ plan et section de la tour T11 |

38/ plan et élévation de l’accès |

39/ reconstitution de la tour T10 |

40/ plan du front ouest et des tours T09, T10 et T11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

41/ rampe d’accès de la tour |

42/ accès principal dans la tour T11 |

43/ accès principal et inscription de construction

n°7 datée 627/1230 |

44/ accès coudé à la forteresse |

45/ tour T12 depuis l’ouest |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

46/ salle de la tour T12 vers l’ouest |

47/ vue du front nord depuis l’accès |

48/ vue de l’intérieur de la forteresse vers l’est |

49/ vue de la citadelle d’orgine à l’extrême est |

50/ les tours T20 et T19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

51/ vestiges sur le front nord |

52/ vue du front sud depuis la citadelle |

53/ vue du front ouest depuis la citadelle |

54/ vue de la tour T09 depuis la citadelle |

55/ vue de la tour T16 depuis la citadelle |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

56/ vue de la tour T15 depuis la citadelle |

57/ vue intérieure de la citadelle entre T19 et T20 |

58/ courtine sur le front sud |

59/ salle de la courtine entre T04 et T05 |

60/ salle sur le front sud |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

61/ courtine entre T05 et T06 |

62/ accès à la tour T07 |

63/ intérieur de la tour T07, côté gauche |

64/ intérieur de la tour T07, côté droit |

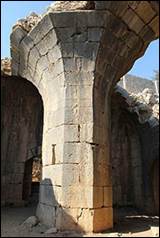

65/ pilier central de la salle dela tour T07 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

66/ vue du front sud vers T08 |

67/ le front sud depuis la tour T08 et la poterne |

68/ vue du front sud depuis T08 |

69/ la fontaine et son inscription vers le réservoir

et la tour T09 |

70/ l’inscription de construction n°10 sur la

fontaine datée 637/1239 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

71/ coupe de la tour T09 |

72/ couloir menant à la tour T09 |

73/ salle de la tour T09 |

74/ salle de la tour T09 |

75/ face sud de la tour T10 avec les inscriptions

déposées et la sculpture de félin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

76/ vue des inscriptions de construction n°13 et

n°15 datées 674/1275 |

77/ vue de l’ensemble des inscriptions déposées |

78/ détail des blocs inscrits de l’inscription n°15 |

79/ détail du début de l’inscription n°15 |

80/ détail du fragment d’inscription n°13 daté

674/1275 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

81/ vue de l’inscription de construction n°11 datée

674/1275 |

82/ vue de l’inscription de construction n°11 datée

674/1275 |

83/ détail du début de l’inscription n°11 |

84/ détail d’un bloc inscrit de l’inscription n°11 |

85/ détail de la fin de l’inscription n°11 |

Documents anciens

Robinson/Smith (1856), I, p.402-404. Visite en 1852.

Leaving Hâzûry we descended to the deep saddle

between it and the castle ; and, climbing a very steep and difficult ascent to

the latter, we kept along the southern wall, and reached, at 1.50, the only

entrance, through one of the southern towers. Here we found ourselves within

the most extensive and best-preserved ancient fortress in the whole country. It

stands upon the eastern and highest point of the thin ridge sliced off (as it

were) from the flank of Jebel esh-Sheikh by the Wady Khŭshâbeh ; and which is connected only with the ridge

of Hâzûry towards the E. S. E. by the saddle just

mentioned. The castle covers this high thin point ; and follows its

irregularities. We estimated its length from east to west at eight hundred or a

thousand feet ; its breadth at each end being about two hundred feet ; while in

the middle it is only from one half to two thirds as broad. The direction of

the ridge is from E. N. E. to W. S. W.

The interior of the fortress is an uneven area of four or five acres. In

some parts the rock still rises higher than the walls ; in others the ground

was now ploughed and planted with tobacco and other vegetables. Here are also

several houses, forming a small village. The fortress was dependent for water

wholly on its cisterns. One of these, in the open area near the western end, is

of immense size ; and even now contained much water. Others are found in

different parts. Besides these, there exists a large reservoir outside of the

castle in the saddle below the eastern end.

The western and lower end of the fortress, which overlooks the whole region

below, exhibits in some parts specimens of the heaviest and finest work. At the

northwest corner especially, large stones lie scattered, which are six or eight

feet in length, finely wrought, and bevelled. Several of the towers along the

southern wall are in like manner finished with superior bevelled work. In

particular, one round tower, with fine sloping work below, presents a finished

bevel at least not inferior to that of the tower Hippicus

at Jerusalem.

The eastern end of the ridge is the highest ; and this was taken advantage

of, to form an upper citadel, commanding the rest of the castle. It is

separated from the lower western portion by a regular interior cross wall, with

towers and trench ; and is without entrance or approach, except through the

lower fortress. Here, more than anywhere, the beetling towers and ramparts

impend over the northern precipice, and look down into the chasm of Wady Khushâbeh six or seven hundred feet below. Within this

citadel are the loftiest and strongest towers ; and this portion is the best

preserved of all. Not less than one third of it is ancient bevelled work ;

exhibiting a better and

more finished bevel, than is perhaps elsewhere found out of Jerusalem.

The Saracens and crusaders made no additions to the fortress. They did

nothing in the citadel, but patch up a few portions of it , where this was

necessary for defence ; leaving all the rest as they found it. Their repairs

are everywhere quite distinct and visible. Nor did they do much more in the

lower or western part. Yet there are quite a number of Arabic inscriptions,

mostly dated about A. H. 625 equivalent to A. D. 1227, recounting that such and

such a prince, with a long pedigree, built up this or that tower at a certain

time.

There are numerous subterranean rooms, vaults, passages, and the like,

which we did not visit. At the western end is a stairway cut in the rock,

descending at an angle of forty- five or fifty degrees. This my companion had

formerly entered for a few steps, and found it choked up with rubbish. Popular

belief, nevertheless, regards it as extending down to the fountain of Bâniâs.

The fortress is not less than a thousand feet or more above the town of

Bâniâs ; and is therefore about equal in elevation to the Kul'at

esh- Shukîf, which towers

in full view over against it. The prospect over the Hûleh and the mountains

opposite is magnificent, though indefinite.

The whole fortress made upon us a deep impression of antiquity and strength

; and of the immense amount of labour and expense employed in its construction.

It has come down to us as one of the most perfect specimens of the military

architecture of the Phenicians, or possibly of the Syro- Grecians ; and whoever will make himself acquainted

with the resources and the prowess of those ancient nations, must not fail to

study the ruins of this noble fortress.

Situated more than two miles distant from Bâniâs , the castle could never

have been built for the protection of that place ; and is not improbably older

than the city. It was doubtless erected in order to command the great road

leading over from the Hûleh into the plain of Damascus. It may have been a

border fortress of the Sidonians, to whom this region early belonged. The

fortress is now ordinarily known to travellers as the castle of Bâniâs ; but

such is not its specific name. Arabian writers speak of it as the Kul'at es-Subeibeh ; but it is

rarely mentioned by them, and mostly in connection with the neighbouring city.

Guérin (1880), II, p.324-327. Visite le 1e novembre 1875.

Le 1er novembre, à six heures du matin, je pars de Banias dans la direction de l'est, puis du nord-est. A six heures quinze minutes, après une montée assez facile, je parviens sur un plateau cultivé en blé. Chemin faisant, je remarque

les traces d'un ancien canal qui amenait au château intérieur de Banias les eaux de la source dite ‘Aïn Kenia, dont il sera question ultérieurement.

A six heures trente minutes, la montée devient plus raide; le sentier serpente à travers de gros blocs de rochers et un fourré de chênes verts et de térébinthes qui ne dépassent pas la hauteur de simples broussailles.

A six heures cinquante minutes, je gravis les marches glissantes d'un escalier étroit taillé dans le roc vif, et à sept heures j'atteins le Kala't Banias, dans lequel je pénètre par une double porte qui ouvre sur la façade méridionale delà forteresse. Celle-ci, tournée de l'est-nord-est à l'ouest-sud-ouest, s'étend sur le sommet rocheux et inégal d'une montagne qui domine de 300 mètres au moins la forteresse de Banias. Elle peut avoir elle-même 450 mètres de

long sur 120 dans sa plus grande largeur. Des ravins extrêmement profonds l'environnent au nord et à l'est, et, de ces deux côtés, lui servent de fossés gigantesques, qui attirent et en même temps épouvantent le regard. Les murs d'enceinte sont très épais et flanqués de nombreuses tours; bâtis intérieurement en blocage, ils sont revêtus à l'extérieur de beaux blocs, les uns complètement aplanis, les autres relevés en bossage, mais la plupart de dimension

moyenne seulement, sauf vers l'extrémité occidentale, où ils sont beaucoup plus considérables. Courtines et tours s'élèvent sur le roc et sont construites en talus. Les tours sont, les unes demi-circulaires, les autres carrées. Quelques-unes sont assez bien conservées et les voûtes en sont ogivales. D'autres sont à moitié ou aux trois quarts écroulées. L'ogive se montre également dans les voûtes de plusieurs grands magasins souterrains et d'un certain nombre

de citernes, parmi lesquelles il en est une très vaste, où l'on descend par un escalier.

A l'extrémité occidentale de l'enceinte on remarque les restes de trois grandes tours carrées, construites avec des blocs énormes et parfaitement taillés. Sur l'un de ces magnifiques blocs, actuellement gisant à terre, on distingue une belle inscription arabe en caractères coufiques, ce qui porte naturellement à penser que l'on a là devant les yeux une restauration musulmane faite avec des matériaux antiques de la plus grande beauté, et comme taille et comme dimensions. Il est difficile, en effet, d'admettre qu'une semblable construction avec de pareilles pierres ne date que de l'époque musulmane. L'une de ces tours renferme un souterrain en partie creusé dans le roc et en partie bâti. A en croire mon guide, il s'étendrait jusqu'à la source de Banias et mettait autrefois cette forteresse en communication avec la ville de Panéas. Cette opinion, comme beaucoup d'autres de cette nature, qui plaisent singulièrement à l'imagination arabe, ne repose, ainsi que je l'ai déjà dit, sur aucun fondement sérieux. Quoi qu'il en soit, après avoir descendu seulement une trentaine de marches, je suis arrêté tout à coup par des éboulements qui m'empêchent de pousser plus avant.

Toute la partie centrale de l'enceinte est bouleversée de fond en comble. On y observe les débris d'une mosquée et quelques fûts de colonnes.

Quant à la partie orientale de cette même enceinte, elle formait, sur le point culminant du plateau de la montagne et au-dessus de la forteresse proprement dite, dont la séparait un fossé creusé dans le roc, une seconde forteresse supérieure, plus inexpugnable encore que la première. Flanquée elle-même de grosses tours, les unes carrées, les autres demi-circulaires, elle surplombait au nord et à l'est les profondeurs effrayantes de l'Oued Khachabeb. Il est

actuellement très difficile de la parcourir, hérissée qu'elle est d'épaisses broussailles et d'un fourré de chênes verts et de térébinthes qui ont pris racine au milieu de l'amas de ruines qu'elle présente. Néanmoins, quelques portions notables de murs et de tours sont encore debout.

Ce donjon se terminait à l'est par une grande salle qui mesurait 30 pas de long sur 10 de large, et dont la voûte détruite reposait sur plusieurs arcades ogivales qui existent encore en partie. Une vaste citerne règne sous cette salle.

Un problème se pose ici de lui-même. Quelle date faut-il assigner à cette puissante citadelle, qui a dû coûter des sommes et des travaux si considérables? Les inscriptions arabes que l'on aperçoit en plusieurs endroits et dont quelques-unes portent la date de l'année 625 de l'hégire, qui correspond à l'année 1227 de notre ère, semblent autoriser à conclure que l'on est là en présence de constructions purement musulmanes; en outre, les voûtes sont presque partout ogivales, ce qui paraît accuser un travail postérieur à l'époque byzantine. Mais, d'un autre côté, comment supposer que les anciens, à l'époque de la plus grande splendeur de cette contrée, aient négligé un point militaire aussi important que celui-là, sur la route conduisant de Tyr à Damas ? Comment attribuer ensuite aux Musulmans la taille de ces immenses blocs, avec les quels avaient été bâties quelques parties de cette forteresse et notamment les trois grandes tours carrées de l'ouest ? N'est-il pas plus rationnel d'admettre que, lorsqu'ils s'emparèrent de ce château fort, ils profilèrent, pour exécuter leurs nouvelles constructions ou réparer celles qui existaient déjà, des nombreux et beaux matériaux qu'ils trouvaient surplace? Les inscriptions arabes, comme je m'en suis plusieurs fois convaincu en Palestine, sont souvent mensongères, en affirmant que tel sultan ou tel prince a élevé une mosquée, un caravansérail ou une forteresse, qu'il n'a tout au plus fait que réparer. Ainsi, par exemple, comme je l'ai montré ailleurs, la fondation de la grande mosquée de Ramleh est attribuée, d'après une inscription arabe placée au-dessus de la porte d'entrée, au sultan Ketbogha, l'an 697 de l'hégire (1298 de J. C.). Or, c'est là une allégation contre laquelle protestent la forme même de ce monument et le caractère de son architecture. On est, en effet, d'une manière incontestable, en présence d'une église chrétienne parfaitement conservée, et non point d'un édifice bâti sur le plan d'une mosquée. Seulement, à l'époque marquée par l'inscription, cette église, consacrée primitivement à saint Jean Baptiste et transformée ensuite en mosquée, a pu subir quelques réparations et modifications.

Pour en revenir à notre forteresse, elle est actuellement désignée sous le nom de Kala't Banias. Dans les auteurs arabes elle est citée sous la dénomination de Kala't es-Soubeibeb. L'historien Joinville l'appelle Subeibe :

« Li chnstiaus, dit-il, qui siet desus la citée a non Subeibe, et siet bien

demie lieue haut es montaignes du Liban, et li tertres qui monte ou chastel

est peuplez de grosses roches aussi grosses comme huges ».

Les Croisés, qui s'en étaient rendus maîtres en 1130, en même temps que de Panéas, la perdirent ensuite ainsi que cette ville, et essayèrent vainement de la reprendre en 1253. Elle est toujours restée depuis entre les mains des Musulmans. Aujourd'hui elle tombe en ruine de toutes parts, et je ne l'ai plus trouvée habitée que par quelques Druses, qui y vivent avec leurs troupeaux.

Wilson (1881), II, p.119-120. Visite entre novembre 1865 et avril 1866.

A little more than one hour from Baniâs is the

great castel of Subeibeh. This has been one of the strongest fortresses in the

East. Its exhibits the work of every period from the early Phoenician to the

time of the Crusaders. Its situation is remarkable, and from its broken walls

one looks across the Huleh Plain to the hills of Galiléé in the west, while at

his feet the mountain-slope descends in terraces that are covered with oaks and

olive-trees. The castle is not far from one thousand feet long by about three hundred

feet in width, and the walls at some points are even yet one hundred feet high.

The natural approach to it is from the east, while it is well-nigh inaccessible

from the south, west, and north. On the north side the mountain, for six

hundred feet below the castle, presents an almost perrpendicular wall before

the bottom of the ravine is reached. The strength of the position has been

greatly augmented by the skill and labour of man, until this might

appropriately be called the Gibraltar of Palestine. Situated at the Southern

base of Mount Hermon, the armies from the East would pass by it on their way to

the sea-coast and Egypt; and the same might be true on their return, as we know

was the case with one of the earliest Eastern invaders, Chedorlaomer, whose

date is at least twenty centuries before the birth of Christ. The cuneiform

inscriptions often speak of Assyrian kings reaching the kingdom of Damascus,

and then entering the kingdom of Tyre. They would be almost compelled to follow

the great highway of the nations on which this fortress stands. The

Phoenicians, no doubt, used all the means in their power to repel these

invaders, and these two facts are suficient to account for the existence of

this castle at this point, while the urgency of the case demanded that it

should be built, with all possible strength. Erom this point two roads diverge,

one leading to Tyre and the other to Sidon. We have found on the road leading

hence to Tyre, Assyrian sculptures which prove the early passing over this route

of their great armies. At the eastern end of this castle stands the citadel of

the place. It has a wall and a moat of its own. It is one hundred and fifty

feet higher than the castle proper, which lies below it to the west. Here one

has an excellent illustration of a fact often mentioned by Josephus and other

ancient writers, that even if the castle was taken in any given case, the

garrison could retire to the citadel and resist the enemy for a long time, if

not with entire success. Such a citadel might best be described as a castle

within a castle, with the difference that the inner one would possess greater

strength and greater means of resistance.

Subeibeh played an

important part in the history of the Crusades, and was often taken and retaken

during those bloody wars between Moslem and Christians. Underneath the ruins,

where we crawled by a difficult passage, we found a stone ball such as were in

common use in ancient siegs. This is a small one, weighing not more than

fourteen pounds, while some that were thrown by the ballistae, as

described by Josephus, weighed at least one hundred pounds. These weapons

corresponded to the heavy artillery of our times, and their destructive power

was very great.

Conder/Kitchener (1881), p.125-128. Visite en

1874-1875.

Kulat

Subeibeh, or Kulat Nimrud (Rb).—The Crusading castle of Banias. This castle was

situated on the crest of a narrow rocky ridge with deep valleys on the northern

and southern sides. It is one of the largest and best preserved ruins of the

sort in the country. The castle was long and narrow, in order to suit the

ground on which it was placed, and the general slope down was from east to

west. The east, being the highest end, was chosen for the citadel, which was

very strongly built : several rooms and vaults of the citadel still survive

almost perfect. The rock was allowed to remain in its natural state, rising

above the towers and walls that protected the castle. At the west end there was

also a citadel and several small towers and barracks, with large cisterns. In

this portion some very large stones were used, measuring as much as 8 to 10

feet long by 4' by 3 feet. These are perfectly dressed, and are drafted,

sometimes with a double draft on a single stone measuring 5" and 7"

or 6" and 7" each. This was certainly magnificent ashlar-work, but

from the key-stone of an arch of this masonry there is no doubt the pointed

arch was used. There is also a pointed arched passage and some vaulted roofed

chambers under this portion. The round towers that protected the walls were

built of smaller drafted masonry, with numbers of masons' marks. The larger

masonry had none. This masonry is well fitted, and, though smaller than the

great blocks of the west end, is very fine work. It probably belongs to

Crusading times, and the towers are made with broad and deep loopholes on the

inside, with pointed arches, like the loopholes at Belfort. The eastern keep

also appears to be Crusading work. The masonry is not drafted in inside work,

or in walls sheltered by other walls ; and this rule was also observable at Belfort and Tibnin. There are

the foundations of a small square building in the centre of the northern side,

with remains of five small columns. This may have been the ancient chapel of

the castle. The only entrance to the castle is by a narrow and steep path that

leads along the southern side of the castle. It enters a square tower by a

Crusading gateway, which opens on to the rocky terreplein of the castle. The

barracks and western towers flank this entrance. The eastern keep is separated

from the rest of the castle by a rocky ditch, and is very strongly built, two

square towers probably guarding a drawbridge. There are cisterns inside the

keep, and many chambers of that portion are still perfect.

Porter (1889), p.132-136. Visite entre 1849 et

1859.

The Castle

of Baneas, or, to give it its proper name, Subeibeh, is among the most imposing

buildings in Palestine. Others, like the Temple of Jerusalem and the Mosque of

Hebron , have more historic and sacred interest attached to them ; but in

commanding situation, extent, and strength, Subeibeh is unrivalled . It crowns

an isolated peak, which rises at least fifteen hundred feet above the town, and

is the most conspicuous object in the neighbourhood. The path up to it is

steep, rugged, and very difficult. It took me a full hour of painful climbing

on a strong and sure - footed Arab horse to reach the gate. I was well repaid

for the toil. The magnificent view alone would repay one. As seen from the

plain of the Jordan on the west, and from the opposite ridge of Naphtali, the

castle appears to stand on the apex of a conical peak ; but on reaching the top

I found that it occupies the culminating point of a narrow ridge, which is

joined by a lower ridge to the mountain chain on the east. The only practicable

road to it from Baneas leads diagonally up the southern declivity of the hill,

then along the summit of the narrow ridge, then up a zigzag path among huge

fragments of rock and thickets of hawthorn and prickly oak and holly to the

foot of the eastern tower, then along a ledge of rock which skirts the southern

base of the ramparts, exposed at all points to missiles thrown from above. We

finally reach a flight of stone steps leading up to a portal in a round tower

at the south- west corner. There is but one entrance, and it is so placed as to

be practically inaccessible so long as the fortress is held by an active

garrison.

The building

covers an irregular area about five hundred yards long from east to west, by

two hundred in greatest breadth. It is narrow in the middle, and bulges out at

each end to suit the shape of the top of the rock. The interior is very uneven.

The natural rock rises higher in places than the encircling walls. The western

end of the castle stands on the very brow of the steep hill, whose sides are in

places scarped to give additional strength. The walls here are very massive,

and apparently of high antiquity. Many of the stones measure from eight to

twelve feet in length, by about four in thickness, and they are drafted along

the edges in a similar manner to those in the Haram walls of Jerusalem and

Hebron. The masonry is very fine, and most carefully executed. Judging by the

examples of similar work I had seen in Jerusalem, Sidon, and Gebal, I concluded

that this part of the castle was at least founded originally by Phoenician

architects.

Whether the

whole of the ramparts are of equal antiquity is doubtful. It is quite possible

that in a much later age the primeval style may have been imitated, though it

is not probable that in the erection of a great fortress in a comparatively

obscure locality so much additional labour and expense would have been incurred

without corresponding advantages. In the interior there are different styles of

architecture, showing the work of diverse ages and races. We find pointed

arches, certainly not earlier than the Crusades, and I saw Arabic inscriptions

of a still later date. But the additions and alterations in the interior afford

no key to the age of the founders of the exterior ramparts.

The round

towers and walls on the south side are built of smaller stones, yet they too

present fine specimens of mural architecture of the style now called Roman

Ashler, the stones being accurately drafted along the edges, with rough

centres. The eastern end of the site is much higher than the western, and

advantage has been taken of this to form a strong citadel, capable of separate

defence. The access to it even now is a work of no little difficulty. There is

a deep moat hewn in the rock across the front of it, and within the moat is a

lofty and strong wall, thus effectually shutting it off from the rest of the

fortress. This inner citadel is the best preserved part of the castle, the

walls and exterior towers being in places almost perfect. Within are vaulted

chambers still habitable ; and there is a small building with columns, which

may have been a chapel in medieval times, when a Crusading garrison occupied

the citadel. An ample supply of water was secured for the garrison by huge

cisterns hewn in the rock, both within the citadel and outside. The

construction and enormous size of the cisterns reminded me of those under the

Haram area in Jerusalem. I was informed by shepherds who take up their abode in

the castle, and pen their sheep and goats in it during part of the hot season,

that they have never known the water in the cisterns to be exhausted ; and

certainly I found most of them well-nigh full during both my visits, one of

which was made in the month of July. The belief is that they are supplied by subterranean

channels from the adjoining hills, where springs are abundant. The cisterns are

mostly deep, unnecessarily so, as I thought, if only intended to collect and

retain surface water.

On the

occasion of my first visit, the castle was utterly desolate. I wandered about

for hours, over its broken ramparts , through its chambers and halls and

corridors, without seeing a human being or hearing a sound save the call of a

shepherd, or the tinkling of a goat's bell away on the distant mountain- side.

Here, quite as fully as out on the Arabian plain, I was able to realize the

poet's words :

" On

desert sands 'twere joy to scan

The rudest

steps of fellow-man,

So here the

very voice of grief

Might wake

an echo like relief-

At least '

twould say , ' All are not gone ;

There lingers life ,

though but in one. ' "

The early

history of the Castle of Subeibeh is unknown. There is no notice of it before

the time of the Crusades. The first record I can find is that it was captured

by the Christian host in the beginning of the twelfth century. But it must have

existed long before that period ; and the fact of its having been besieged and

taken after a hard struggle shows that it was then a place of importance and

strength. Its position commanding the city of Baneas, and the great road from

the rich valley of the Jordan to Damascus, made its possession of great

strategical value. We know that from the very earliest times the Phoenicians

held the city of Dan and the surrounding plain ; they would

therefore

naturally desire to strengthen their position there, and to defend one of their

principal granaries from hostile tribes of the eastern desert. And no spot was

more suitable for defence than the peak of Subeibeh. Subsequent to its capture

by the Crusaders it passed through the customary varied fortunes of Syrian

strongholds – now taken by Moslems, now by Christians, each destroying,

repairing, or rebuilding, as best suited their purpose. Nureddin, father of the

more famous and better-known Saladin, took it by storm in 1163 ; and

thenceforth the Crescent waved over its battlements, until it was abandoned in

the seventeenth century. Since then it has been unoccupied, except occasionally

and temporarily by a few goatherds. The solidity of its walls alone has

prevented that utter ruin which we have noticed in other towns of Galilee. Had

it not been for the earthquakes, which have committed such fearful ravages on

the towns and villages of this district, the Castle of Subeibeh might still

have remained perfect almost as when built ; but no strength of wall can resist

the terrible shock of an earthquake.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Plan de la forteresse d’après le Survey of Western

Palestine (1874-1875) Source : Conder/Kitchener (1881) |

Vue de la tour T07 depuis l’ouest Source : Conder/Kitchener (1881) |

Vue des tours T01 et T16 depuis l’est Source : Wilson (1881), II |

Vue de la citadelle depuis l’ouest avec les tours

T20 et T19 Source : Wilson (1881), II |

Vue de la forteresse depuis l’ouest Source : Porter (1889) |

|

|

|

|

|

Vue du front sud depuis l’ouest vers 1910 d’après

l’American Colony Photo Department Source : Library of Congress |

Vue de l’intérieur du site depuis l’ouest vers 1910

d’après l’American Colony Photo Department Source : Library of Congress |

Vue de la citadelle depuis l’est vers 1910 d’après

l’American Colony Photo Department Source : Library of Congress |