Jisr Jindas/pont sur Nahr Ayalon (671/1273)

Localisation : pont sur le Nahr Ayalon, actuelle rue Mordechai Frieman au nord du rond point.

Réf :

Clermont-Ganneau (1887), p.496-527

Clermont-Ganneau (1888), p.262-279

Clermont-Ganneau (1896), II, p.110-117

Meinecke (1992), 4/175

Clermont-Ganneau (1887), p.496-527

Clermont-Ganneau (1888), p.262-279

Mayer (1933), p.109

RCEA 4660, 4661

TEI, n°2297, 2298

Tütüncu (2008), n°238, 239

Historique

Ce pont à triple arches franchit le Wadî Musara/Nahal Ayalon au nord de Lod, sur l’ancienne route de Ramla. Il est attribué au sultan Baybars (r.17 dhu’l-qa’da 658/24.X.1260 – 27 muharram 676/30.VI.1277), identifié grâce aux lions/panthères représentés de part et d’autre des deux inscriptions de construction (ill.5, 8). Il est probablement érigé en même temps qu’une série de ponts construits par le sultan sur les principaux cours d’eau de l’époque dont le pont de Yavne et le pont de Ashdod sont toujours debout.[1]

Il est daté de ramadan 671/22.III-20.IV.1273, mais il n’est achevé qu’en 672/1273-1274 sous la conduite de ‘Alâ’ al-Dîn ‘Ali al-Sawwâq qui a aussi supervisé les travaux de restauration de la Grande Mosquée après la prise de Jaffa par le sultan Baybars le 20 jumada II 666/6.II.1268.

Il a été étudié par Ch. Clermont-Ganneau lors de sa mission en Syrie entre novembre 1873 et novembre 1874.[2]

Epigraphie

671/1273. Texte de construction 4 lignes sur la face amont (ill.6).[3]

« xxx la construction de

ce pont béni a été ordonnée par notre maître le sultan auguste al-Malik

al-Zâhir Rukn al-Dîn Baybars, fils de ‘Abd Allah, durant les jour de son

enfant, notre maître le sultan al-Malik al-Sa’îd Nâsir al-Dîn Baraka-khân, que Dieu

glorifie leurs victoires et leur pardonne ! cela (fut achevé) sous la

direction de l’esclave avide de la miséricorde de Dieu ‘Alâ al-Dîn ‘Alî

al-Sawwak – que Dieu lui pardonne ainsi qu’à ses père et mère ! – dans le

mois de ramadan de l’année 671 (mars-avril 1273) ».

671/1273. Texte de construction 4 lignes sur la face aval (ill.8).[4]

« xxx la construction de

ce pont béni a été ordonnée par notre maître le sultan auguste al-Malik

al-Zâhir Rukn al-Dîn Baybars, fils de ‘Abd Allah, durant les jour de son

enfant, notre maître le sultan al-Malik al-Sa’îd Nâsir al-Dîn Baraka-khân, que Dieu

glorifie leurs victoires et leur pardonne ! cela (fut achevé) sous la

direction de l’esclave avide de la miséricorde de Dieu ‘Alâ al-Dîn ‘Alî

al-Sawwak – que Dieu lui pardonne ainsi qu’à ses père et mère ! »

Biblio complémentaire

Petersen (2001), n°65

Petersen (2010), p.291-306

Czitron (2019)

Czitron (2020), p.21-48

Gat (2020), p.9-20

|

|

|

|

|

|

1/ plan et relevé du pont |

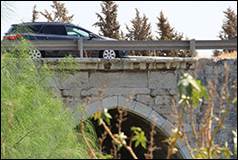

2/ vue du pont en amont |

3/ face amont du pont depuis le sud |

4/ face amont du pont depuis le nord |

|

|

|

|

|

|

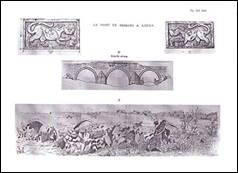

5/ l’arche centrale du pont avec l’inscription et

son décor |

6/ l’inscription de construction datée 671/1273 |

7/ face aval du pont |

8/ l’inscription de construction datée 671/1273,

côté aval |

Documents anciens

Clermont-Ganneau (1896), II, p.110-117. Visite

en juin 1874.

The fine church erected by the Crusaders in

honour of their much-venerated Saint, by the side and at the expense of the

Byzantine church, was, as I have said, destroyed by Saladin. Though history is

silent as to its later fate, it still had one most strange experience. As I

thought I noticed already in 1871, part of the material used in building it was

carried in the thirteenth century to the distance of a mile, and set up again

to build a bridge over the wady which runs to the north of Lydda, and joins the

numerous wadys that have their outlet at Jaffa.

Wishing to determine with exactness under what

circumstances this removal took place, I resolved to make a detailed plan of

this bridge. I enjoyed the aid of M. Lecomte in this, and was very glad to have

his valuable opinion on many technical points. This thoroughly bore out my own

conclusions.

This bridge, above 30m. long and about 13m. broad, is composed of three pointed arches nearly equal in height, a central arch about 6"50 across, and two lateral ones about 5m. The bed of the wady over which it is thrown is entirely dry in summer, but a considerable volume of water passes along it at the period of the winter rains. It is to some extent blocked up by patches of alluvial earth, on which there grow prickly-pear-trees (saber). On the side facing up stream, the two central supports are protected by two pointed cut-waters intended to break the force of the current, which must be very violent in time of flood.

Above the central arch, in a rectangular slab, that is sheltered by a projecting marble cornice, is an Arabic inscription of four lines, Hanked by lions.

On the other side (looking down stream) of the same central arch is set another Arabic inscription of three Hnes, a repetition almost word for word of the preceding, barring a few slight variations ; it is likewise sheltered by a

marble cornice and flanked by similar lions. Here follows the transcription and translation of the first.

« In the name of the kind and merciful God, whose blessings be on our Lord Mahomet, on his family, and on all his companions ! The building of this holy bridge was ordered by our master, the very great Sultan el Malek edh-Dhaher Rukn ed Din Beibars, son of 'Abd Allah, in the time of his son our Lord Sultan el Malek es Sa'id Naser ed Din Berekeh Khan, may God glorify their victories and grant them both His grace. And this, under the direction of the humble servant aspiring to the mercy of God, 'Ala ed Din 'Aly es Sawwak, to whom may God grant grace as also to his father and mother ; in the month Ramadan, the year 671 ».

The month Ramadan, 671a.h., corresponds to March-April, 1273 of our era. The famous sultan Beibars had only four years before associated his son Berekeh Khan with him in the kingly power ; hence the mention of him in our inscription along with his father, while he does not appear on the inscription of Beibars at Ramleh, dated 666 ; the act of taklid, investing the young Berekeh Khan with the royal power, having been first promulgated a year later, in 667.

The two inscriptions are flanked by a pair of low bas-reliefs poorly cut, each displaying a lion seen in profile, enclosed in a rectangular frame. The two animals, which are similar on either side of the bridge, face one another in the same attitude, "passant" and "leopard" to speak heraldically. They are indifferently executed in pure Arab style. The lion on the right has his right paw raised ; in front of him, beneath the threatening claws, sits a tiny quadruped, seen in profile, which, from its pointed nose and ears as well as its long tail bent vertically along its back, can only be taken for a rat or squirrel, or perhaps a jerboa (?). The little creature has its front paws stretched out towards the lion, apparently in an attitude of entreaty.

The lion on the left is lifting his left paw. In front of him is a small quadruped, obviously a repetition of the former one. The characteristic long tail of the animal does not appear in the drawing, but exists in the original ; only in this case it is bent back between the hind paws and lies along the right thigh.

These representations recall those oriental apologues wherein the lion and the rat appear, and perhaps contain some allusion to the repeated victories of Sultan Beibars over the Crusaders, whom he crushed in several encounters,

and successively deprived of Cresarea, Arsuf, Safed, and lastly Jaffa, the neighbour town to Lydda. Can there be some play in the words fâr "rat" and kuffar "the infidels ?" or is it intended to caricature the lion rampant, the device of the Lusignans, kings of Cyprus and Jerusalem, by representing it as a rat ?

In any case, these lions are of singular interest for the history of heraldry among the Mussulmans. We know from Arabic writers that the rank or "heraldic emblems" of Sultan Beibars was a lion, and I have found that animal on numerous structures in Syria and Egypt raised by that sovereign.

It is also represented on his coins, both gold, silver, and bronze.

Beibars was a great bridge-builder. I have noted in Arabic chronicles quite an imposing number of these structures executed by his orders. That at Lydda is expressly mentioned by the anonymous author of the Life of Beibars, who speaks of "two bridges built by Beibars in 672, in the neighbourhood of Ramleh, to facilitate the passage of troops." The agreement of the dates denotes that one of the two bridges is ours. Another remains to be discovered in these parts. My first thought was of the jisr al-Sudda, which is three miles further to the north, but I now incline to another opinion, which 1 will enunciate latent The chiefly strategic object of these two bridges proves that they were intended to ensure a permanent communication along the highway between Egypt and Northern Syria, which passed through Ramleh and Lydda, and was cut up by numerous wadys originating in the Judaean highlands.

It was especially important to Beibars, as the requirements of war and politics continually summoned him from one end of the kingdom to another during his victorious struggle against the Crusaders and his native rivals, and

he had need of solid bridges to secure a way at all seasons across the wadys that intersected his route, not only for men and horses but also—which was most important—for baggage and siege artillery (manjanîk).

In the case of the bridge of Lydda, Beibars had an immediate and special interest in making safe the north road from Lydda, so that his troops could move rapidly forward and cover Ramleh, Lydda, and the plain as far as Carmel, in cast! of a hostile movement on the part ot the Crusaders. In 1271 Prince Edward of England had pushed a daring raid as far as Kakun, thus threatening Lydda. Here was a danger to be guarded against, more especially as Prince Edward had refused in person to subscribe to the truce of Cesarea formed in 1272 by Beibars with King Hugh, thinking to renew the incursions that he had found so profitable. Beibars adopted two measures, first he tried, in 1272, to get rid of the English Prince by assassination, and oddly enough it was the Emir of Ramleh who prompted him to this base attempt, which was disavowed by Beibars, after its failure, as an excess of zeal. Secondly (in 1273) he built the bridge of Lydda. The coincidence in date between these two occurrences is most significant, and points to a close relationship between them.

Apparently then everything concurs to persuade us that the bridge of Lydda was of pure Arab origin ; and yet, as I have already pointed out, a close examination reveals a most unexpected archaeological fact—the greater part of the materials of the bridge of Beibars are of Western origins. The stones display the mediaeval slanting tool-marks, an infallible indication of the work of the Crusaders ; moreover, many of them bear masons' marks that are absolutely conclusive. For instance, several stones of the central arch have the W- In the special Table of Vol. I will be found a series of these marks which I noted, and there are certainly plenty more that must have escaped me. They may all be found on the stones of the church of Lydda that have remained in their old position.

The outline of the mouldings of the marble cornices that overhang and protect the bas-reliefs, and the Arabic inscriptions, are anything but Arab in style. We could not take a drawing of these, so as to compare the outlines with that of the mouldings in the church at Lydda. We ought, likewise, to have satisfied ourselves that it did not display the mediaeval tool-marking. Happily, I am in a position to fill up this lacuna, thanks to the kindness of M. van Berchem, who has been so good as to verify this detail carefully at my request. I cannot do better than to transcribe here, in a shortened form, the notes that he has sent me :

" The cornice over the inscription (on the side looking up stream) appears to be Latin, but it is smooth, and made of polished marble without strins (a). This cornice is of different workmanship from the one with the inscription, and from the lions ; it is of marble, instead of the coarse-grained limestone worked by the Arabs. The corresponding cornice on the down side has a profile like this (b).

The surface has strix very slightly slanting, and almost horizontal, having their direction determined by the concave-convex surface of the doucine.

Lastly, the central pointed arch, instead of having a keystone, as is the case with all Arab ogives, has the vertical joint passing through the middle.

Now it is a matter of common knowledge that the vertical joint is the mark of a specific difference ! between the arch of the Westerns—three-centered—and the Arab arch. From a statical point of view the two arches are constructed on quite different principles. The Arab pointed arch, with its keystone, is in a sense an imitation semi-circular arch. While we are dealing with this matter, I should like to draw attention to a curious point of relation hitherto unnoticed. The tiers point or three-centered arch, commonly called now-a-days by French architects the ogive, sometime also in mediaeval language went by the name of five-centered arch or quint point. Now when I was at Jerusalem I heard natives—men engaged in the trade—call the pointed arch, as opposed to the semi-circular arch, Khûmes, "fifth" which answers exactly to the mediaeval name of quint point of five-ccntered.

I will add a few more remarks which I owe to M. van Berchem, and which are a further confirmation of the preceding, or serve to make them more precise.

"The two "heads" of the middle arch consist of striated blocks, much better set up than those of the main part of the bridge. The latter is of small tufous rubble, mixed with striated blocks. The two side arches are also of small rubble (Arab dressing) ; however, these arches also present a vertical joint, like the middle arch, with the exception of that on the west, which has on the north side an Arab keystone . . . The central arch (Crusaders' materials) shows all along its edge a quadrant-shaped moulding ; now on several of the blocks of the head of the arch this moulding occurs again, not only on the outside, at a, but also on the inner edge at b, in the intrados, which proves that they originally formed part of an " arc doubleau " or a Gothic rib, and would tend to confirm your hypothesis, which appears to me altogether probable."

Though the materials are of mediaeval origin, it was certainly not the Crusaders who built this bridge. The patches, bad joins, unevennesses, and faulty dressing of the stone which are visible in the setting up of these heterogeneous materials betray the process of working up that they have evidently been through." Besides, the bridge is nowhere mentioned in the annals of the Crusaders, and Beibars loudly claims the honour of having built it. He speaks truly, but what he omits to say is that the person charged by him to construct with all speed this much needed bridge, hit upon the idea of making a quarry of the ruins of the Crusaders' church demolished by Saladin nearly a century before. The central arch of the bridge, at any rate, is simply one of the arches of the church, indifferently set up. In the main part of the structure there are even tambours of half-columns imbedded in the pilasters, with their masons' marks on each tambour. Thus the bridge of Lydda forms a necessary complement to the church, which explains why I have thought it desirable to submit it to a detailed examination from an historical as well as an archaeological standpoint.

This bridge goes by the name of "Bridge of Jindas" (jisr Jindâs) among the natives, from the name of a small village lying quite near it to the east. According to a local tradition which I heard at Jindas itself, the origin of the village only dates back to the construction of the bridge, that is to say to 1273.

This tradition seems at first sight to be in flagrant contradiction with a Latin charter of 1129, which mentions the "casal" of Gendas in the territory of Lydda, most certainly identical with our Jindas. This is 144 years before the building of the bridge by Beibars.

However, the tradition may be perfectly well founded, and not incompatible with fact.

The truth is, it strikes me as more than probable that the bridge itself is not, any more than the stones which to-day compose it, the work of Arabs in the first instance. I discovered inside one of the small lateral arches (that on the right as you look at the side facing up stream) the remains of a ruined arch of still earlier date. The springs of it are marked A-B on geometrical elevation. This arch was semi-circular as appears from a calculation of the curve. The keystone must have been more than 13 feet below the intrados of the ogive arch which surmounts it at the present day. This difference in level is the result of the gradual filling-up of the bed of the wady by alluvial deposits, which would point to a considerable interval, certainly some centuries, between the construction of these two bridges, quite different in form.

It may well be supposed that long before the thirteenth century, perhaps as early as the Roman, or at least the Byzantine period, there was already a bridge at this point, which lies on an important highway of Palestine, that uniting Lydda (Diospolis) and Csesarea by way of Antipatris. The Arab bridge was founded on the remains of this ancient one, and probaby at one time or another the hands of the Byzantines also were busy with the latter.

It is not impossible that the old bridge of Lydda is the place alluded to in the Talmud, in speaking of the copy of the Torah that was burnt by the sacrilegious Apostomos, that is, if we really must follow the commentators in rendering the words Ma'abartha de Lod, by "the bridge of Lydda."

In any case these facts enable us to understand how the inhabitants of Jindas can assert, without grievous error, that their village, though mentioned at least as early as the twelfth century, was contemporary with a bridge which

at first one would not suppose to have existed before the end of the thirteenth, since this bridofe dates back much earlier than the thirteenth or even the twelfth century. Jindas therefore may very well be contemporary, as local

tradition has it, with this ancient Byzantine or Roman bridge.

This name Jindas has not an Arab or even a Semitic appearance. Possibly it may be merely a corruption of the male name, which was common enough in the Byzantine era. Gennddios, or Gennddis, as the pronunciation was in Syria at that period, would be regularly transliterated into Arabic as Jenadis ; there exists about ten miles from Lydda, to the north-east and quite near 'Abbud, a locality bearing the latter name. I allude to the Mughr Jinâdis of the Map (Sheet XIV, kq).

Jenadis looks like a plural form of Jindas, but it is quite within the bounds of possibility that it was just this look which produced the corrupt form Jindas, and that this later on was artificially constructed as a singular out of the

primitive type Jenâdis, which has the air of a plural. So Jisr Jindas may mean simply the bridge of Gennadios, some more or less official personage of the Byzantine period, who, we may suppose, attached his name to the construction or reconstruction of the bridge of Lydda and from the bridge the name may have passed on to the neighbouring village.