Citadelle de Bosra/Qal’at Busra (n.d.)

Localisation : théâtre romain au sud de la vieille ville (plan n°10).

Visite en 2006.

Réf :

Aalund/Meinecke (1990), n°25

Abel (1956), p.95-138

Brünnow/Domaszewski (1909), p.44-84

Buckingham

(1825), p.202-207

Burckhardt (1822), p.233

Butler (1914), p.295

Korn (2004), p.174-180

Meinecke (1992), 4/3

Seetzen

(1854), I, p.68

Schumacher

(1897), p.146-147

Brünnow/Domaszewski (1909), n°7, 8, 28

Guérin (2002), n°64, 65, 67, 69, 71, 75, 78, 79, 80, 81

Littmann (1949), n°45, 46, 47, 48, 50

RCEA 3548, 3686, 3724, 3755, 3818, 3819, 3884, 3983, 4037, 4308

Sharon (2007), p.49-53

TEI, n°2950, 2989, 3022, 3084, 3085, 4056, 4156, 4308, 8343, 30741, 33673

Historique

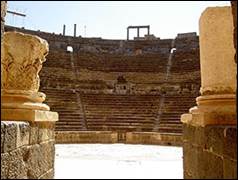

Cette citadelle, de plein pied, a pour particularité d’enchâsser le théâtre romain de la ville. Elle est le fruit de plusieurs phases de constructions, sa forme actuelle date principalement de la période Ayyûbide, elle propose aussi des nouveautés dans son aménagement qui serviront de modèle à de futures fortifications (ill.1).

La plus ancienne preuve de travaux est documentée par une inscription datée 481/1089[1], trouvée aux pieds de la tour T01, au nom de Kumushtakin, le gouverneur Seljukîde de la citadelle. Elle concerne la construction des tours T01 et T02.

Une campagne de fortification est menée par Mu’in al-Dîn, c’est lui qui va commencer à entourer le théâtre romain avec les tours et courtines de la future citadelle, ces travaux sont mentionnés sur l’inscription datée 542/1147[2] à la base de la tour T03.

Période Ayyûbide

C’est au sultan Ayyûbide al-‘Adîl (r.592/1196-615/1218) que l’on doit la forme définitive de la citadelle. Celui-ci entame une grande campagne de travaux s’étalant de 599/1200 à 618/1218, qui doivent faire de Busra un point sécurisé au sud de la principauté de Damas.

Il construit alors une série de courtines et de tours séparés du théâtre par un couloir de circulation.

Ces travaux se déroulent en plusieurs phases :

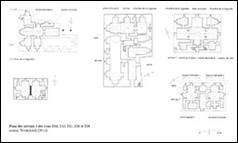

A partir de 599/1203 : construction des tours rectangulaires T06 (ill.7, 8, 18), T08 (ill.3-5, 18) et de la tour en L T04 (ill.12, 13, 18), ces tours sont similaires à celles de la citadelle de Damas, en travaux à la même période.

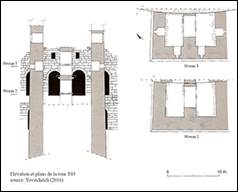

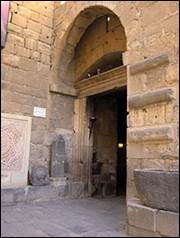

608/1211-610/1213 : construction des tours T09, T10 et de l’entrée coudée (ill.2, 16, 17, 19).

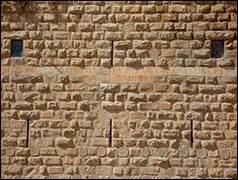

612/1215-615/1218 : construction des tours T05 et T11. Leur aménagement intérieur, novateur, sera reprit sur certaines tours des citadelles de Damas, du Caire et de Baalbek.[3] On note aussi un changement de tailles des assises (ill.10, 11, 14, 18).

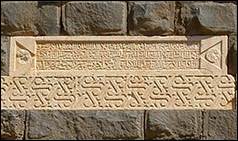

Ces travaux du sultan al-‘Adîl sont tous documentés par des inscriptions (inscriptions n°1-6).

Les successeurs d’al-‘Adîl, dont al-Sâlih Isma’îl (r.635/1237-635/1238 et 637/1239-643/1245), poursuivent les travaux en renforçant la base de certaines tours avec un glacis, ces travaux étant datés de 638/1240 par l’inscription sur la tour T04. Au centre du théâtre, il fait construire un énorme édifice, attesté par des inscriptions (inscriptions n°7-9) avec une citerne, une mosquée (620/1223), une caserne (625/1227) et un arsenal (629/1232). Ce bâtiment a été démoli dans les années 1970.

Enfin al-Sâlih Ayyûb (r.648/1250-658/1260) réhaussera la tour T06 en 647/1249 et al-Nâsir Yûsuf (r.636/1239-637/1239 et 643/1245-647/1249) la tour T08 en 649/1251.

Période Mamluk

La conquête des Mongoles ne porte pas un coup fatal à la citadelle, ceux-ci se contentent seulement de la désarmer en rasant le couronnement des tours et courtines. Du coup, lors de la reconquête du site par le sultan al-Zâhir Baybars en 659/1260, la citadelle ne fait pas l’objet de grands travaux de restaurations. On notera un réhaussement de la courtine C11-10 (ill.15) et quelques opérations mineures sur le système défensif. La tour T07 daterait aussi de cette période (ill.6).

Epigraphie

599/1203. Texte de construction sur la tour T04 (inscription n°1).[4]

« Dieser Burg heisst

der begründete Sieg und er wurde gebaut in den Tagen des Königs Abû Bakr ibn

Aiyûb und seines Sohnes des Königs ‘Isa. Der Grund wurde gelegt im Jahre 599

(1203) ».

608/1211. Texte de restauration 5 lignes (90x50) dans un cadre à queues d’aronde sur la face est de la tour T10 (inscription n°2).[5]

« xxx La fondation de

cette tour et de la porte bénie a été ordonnée par notre maître le sultan

al-Malik al-‘Adîl Saif al-Dîn Abû Bakr, fils d’Aiyûb, l’mai dévoué de l’émir

des croyants, - que Dieu éternise sa royauté ! – sous la surveillance du

très illustre émir, le grand maréchal, Rukn al-Dîn Mankuwirish, affranchi du

maître Falak al-Dîn, frère du sultan, - que sa victoire soit glorieuse ! –

en l’année 608 (1211) ».

610/1213. Texte de construction 5 lignes dans un cadre à queues d’aronde sur le tour T09 (inscription n°3).[6]

« xxx La construction de

cette tour bénie a été ordonnée par notre maître al-Malik al-‘Adîl Saif

al-dunya wa’l-dîn, le subjugueur des infidèles et des polythéistes, le

souverain des deux nobles sanctuaires, de Jérusalem, de la Syrie, de l’Egypte,

du Yémen, de Khitât, des Khoï et de Salmas, Abû Bakr, fils d’Aiyûb, l’ami

dévoué de l’émir des croyants, sous l’administration de l’émir Rukn al-Dîn

Mankuwirish, fonctionnaire d’al-Malik al-‘Adîl et de Falak al-Dîn (?). le début

de sa construction eut lieu en jumada II de l’année (60)9 (novembre 1212), et

la fin le dernier jour de safar, des mois de l’année 610 (20.VII.1213) ».

612/1215. Texte de construction, 6 lignes (110x90), sur la face nord de la tour T11 (inscription n°4).[7]

« xxx La construction de

cette tour bénie a été ordonnée par notre maître al-Malik al-‘Adîl, le champion

de la foi, le combattant, Saif al-dunya wa’l-dîn Abû Bakr, fils d’Aiyûb, l’ami

dévoué de l’émir des croyants, - que Dieu glorifie ses victoires et double son

pouvoir ! – sous l’administration de l’avide de la miséricorde de Dieu,

Rukn al-Dîn Mankuwirsih, fils de ‘Abd-Allâh, serviteur d’al-Malik al-‘Adîl et

d’(al-Malik) al-Mu’azzâm, - que Dieu le soutienne ! – et sous la

surveillance de l’émir Shihâb al-Dîn Ghazî, fils d’Aibak al-Ruknî, que Dieu le

glorifie ! Cela (a été achevé) dans les mois de l’année 612 (1215) ».

615/1218. Texte de construction 3 lignes (200x40), plaque en marbre blanc à queues d’aronde sur la face sud-ouest de la tour T05 (inscription n°5, ill.11, 31).[8]

« xxx La construction de

cette tour bénie a été ordonnée par notre maître al-Malik al-‘Adîl, le champion

de la foi, le combattant, Saif al-dunya wa’l-dîn, le sultan des musulmans, Abû

bakr, fils d’Aiyûb, l’ami dévoué de l’émir des croyants, sous l’administration

de l’avide de la miséricorde de Dieu, Rukn al-Dîn Mankuwirish, fils de

‘Abd-Allâh, serviteur d’al-Malik al-‘Adîl et sous la surveillance de l’émir

Shihâb al-Dîn Ghazî, fils d’Aibak al-Ruknî, que Dieu le glorifie ! Cela (a

été achevé) dans les mois de l’année 615 (1218) ».

615/1218. Texte de construction 3 lignes (30x50) encastré dans l’angle de la tour T11 (inscription n°6).[9]

« xxx L’extraction de

cette pierre d’angle, de la grande vallée. Son arrivée en ville eut lieu, au

milieu du jour, sous la surveillance de Shihâb al-Dîn ».

620/1223. Texte de construction 4 lignes dans un cadre à queues d’aronde sur l’ancienne mosquée de la cavea (inscription n°7).[10]

« xxx Notre maître le

sultan al-Malik al-Sâlih [‘Imad] al-Dîn Abul-Tahîr, I[sma’îl], fils d’al-Malik

al-[‘Adî]l [Saif] al-Dîn [Abû Bakr], fils d’Aiyûb, ami de l’émir des croyants,

a ordonné de construire cette mosquée bénie, sous le gouvernement de l’émir

Badr al-Dîn Dawûd, fils d’Aidakîn, serviteur d’(al-Malik) al-Sâlih (Isma’îl),

en l’année 620 de l’hégire du Prophète (1223) ».

625/1228. Texte de construction 6 lignes sur un pilier de l’ancienne caserne+ (inscription n°8).[11]

« xxx La construction de

cette voûte bénie a été ordonnée par notre maître le sultan al-Malîk al-Sâlih,

le seigneur très illustre, le juste, le champion de la foi, le vainqueur,

l’assisté de Dieu, xxx, en l’année 625 (1228), sous la direction de l’émir Badr

al-Dîn Dâwûd, fils d’Aidakîn al-‘A[dilî] xxx al-Sâlihî, que Dieu glorifie par

lui xxx des musulmans (?) ».

629/1232. Texte de construction 4 lignes (170x80) sur le linteau de la porte du vestibule de l’arsenal+ (inscription n°9).[12]

« xxx La construction de

ce magasin d’armes béni a été ordonnée par notre maître le sultan al-Malîk

al-Sâlih, le savant, le juste, ‘Imad al-Dîn Abûl-Fida’ Isma’îl, fils d’al-Malîk

al-‘Adîl Abû Bakr, fils d’Aiyûb, - que Dieu ait pitié de lui ! – sous la

direction de l’émir Badr al-Dîn Dâwûd, fils d’Aidakîn, le précepteur

d’(al-Malîk) al-Sâlih, dans les mois de l’année 629 (1232) ».

640/1242. Texte de construction découvert dans les déblais (inscription n°10).[13]

Texte non disponible.

647/1249. Texte de construction, bandeau sur les 3 faces de la tour T06 (inscription n°11, ill.7).[14]

« xxx Gloire à notre

maître le sultan, le seigneur très illustre, al-Malîk al-Sâlih Najm al-dunya

wa’l-dîn Abul-Muzaffar Aiyûb, fils d’al-Malîk al-Kâmil Muhammad, fils d’Abû

Bakr, fils d’Aiyûb, le sultan de l’Islam et des Musulmans, le subjugueur des

infidèles et des polythéistes, le vivificateur de la justice dans les mondes,

celui qui rend justice aux opprimés contre les oppreseurs, le potentat de la

Syrie, le sultan des Arabes et des Persans, le possesseur des deux sanctuaires

sacrés, le roi des deux continents et des deux mers, le roi de l’Inde et du

Sind, du Yemen, le roi de San’a’, de Zabîd et d’Aden, le seigneur des rois des

Arabes et des Persans, le sultan des Orients et des Occidents, le roi auguste

Najm al-dunya wa’l-dîn, que Dieu fasse durer ses jours, déploie ses étendards

sur les deux horizons, et double son pouvoir, par Mahomet et sa famille !

Voici qui a été fait sous la direction de l’émir très illustre Shuja’ al-Dîn

‘Anbar al-Sâlihî, en l’année 647 (1249) ».

649/1251. Texte de construction sur la face sud-est de la tour T08 (inscription n°12, ill.5, 30).[15]

Texte non disponible.

Biblio complémentaire :

Yovitchitch (2001)

Guérin (2002), p.229-279

Korn (2004)

Yovitchitch (2004), p.205-219

Aalund (2005), p.21-54

Dentzer-Feydy (2007), p.179-189

Dotti (2007), n°10

Yovitchitch (2007), p.421-467

Yovitchitch (2007a), p.179-188

Hartmann-Virnich (2008), p.299-302

Yovitchitch (2008b), p.169-177

Yovitchitch (2011)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1/ plan de la citadelle |

2/ vue depuis l’est |

3/ la tour T08 avec son inscription |

4/ la tour T08 avec son glacis |

5/ la tour T08 et l’inscription datée 649/1251 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

6/ les tours T07 et T06 |

7/ l’inscription datée 647/1249 de la tour T06 |

8/ la tour T06 à droite, l’orillon

et T03 |

9/ plan de la tour T03 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10/ la tour T05 |

11/ la tour T05 et l’inscription datée 615/1218 |

12/ la tour T04 depuis le sud |

13/ la tour T04 depuis le nord avec

la courtine C4-11 |

14/ la tour T11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

15/ la courtine C11-10 et T10 à

droite |

16/ la tour T09 et l’accès |

17/ plan des tours T10 et T09 |

18/ plan des étages des tours T04,

T10, T11, T06, T08 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

19/ l’accès entre les tours T09 et

T10 |

20/ couloir de circulation entre à gauche le théatre

et à droite la tour T05 |

21/ à gauche la tour T03, au fond

T06 depuis l’orillon |

22/ couloir de circulation entre à gauche le théâtre, à droite les tours T07 et T08 |

23/ série d’archères sur une courtine du couloir de

circulation |

|

|

|

|

|

24/ vue du théâtre depuis les

gradins |

25/ la scène depuis l’est |

26/ la scène et les gradins depuis

l’ouest |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

27/ la scène et la cavea sur

l’arsenal depuis l’ouest |

28/ les gradins depuis l’ouest |

29/ les gradins depuis la scène |

30/ le bandeau inscrit daté 649/1251 de la tour T08 |

31/ l’inscription datée 615/1218 de la tour T05 |

Documents anciens

Burckhardt (1822), p.233. Visite le 27 avril 1812.

I now quitted the precincts of the town, and just beyond the walls, on the S. side came to a large castle of Saracen origin, probably of the time of the Crusades : it is one of the best built castles in Syria, and is surrounded by a deep ditch. Its walls are very thick, and in the interior are alleys, dark vaults, subterraneous passages, &c. of the most solid construction. What distinguishes it from other Syrian castles, is that on the top of it there is a gallery of short pillars, on three sides, and on the fourth side are several niches in the wall, without any decorations ; many of the pillars are still standing. The castle was garrisoned, at the time of my visit, by six Moggrebyns only. There is a well in the interior. […].

Buckingham (1825), p.202-207. Visite mi-mars 1816.

The exterior of the castle is in the rustic masonry of the Romans, which might, however, have been adopted and used by the Saracens : but here, as in most of the other large castles that I had seen in this country, there was a mixture of styles which rendered it exceedingly difficult to say in what age or by what people they were constructed. Just before the entrance to this was a small guard-house, with a fan or shell-topped niche, of good sculpture, with a column on each side, such as is frequently seen in Roman ruins generally, and is often met with in the remains at Jerash ; while on the walls of the castle itself is a long Arabic inscription, dated in the year of the Hejira, 722, which is, of course, Mohammedan.

Reverting to the singular mixture of styles and ages in the same building, after I had copied the Greek inscription, observed the Roman niched guard-house, and remarked the Arabic lines on the castle walls, we came, on the inside of the gate of entrance, to a piece of decidedly Roman sculpture, in the architrave of a doorway, with a circular wreath in the centre of it, and near this another Greek inscription […].

Proceeding further into the interior of the castle, the following inscriptions were met with, the first on a stone altar, and the second over a door-way […].

In the very centre of the castle I was at once surprised and delighted by our coming suddenly upon a fine Roman theatre, apparently of great extent and beauty in its original state, though now so confounded with other ruins that it was difficult to say whether the castle was originally a Roman work, with this theatre in its centre for the entertainment of the garrison and such other guests as might be admitted from without, or whether it was a Saracen work built upon the ruins of a Roman theatre previously standing on this spot. It was an interesting problem, but it would require a more careful examination than my hurried moments would admit to secure its solution, so that I content myself with merely stating that this subject of enquiry was one that instantly presented itself to my mind, on first seeing these undoubted remains of Roman luxury, art, and pleasure, enveloped, as they might now be said to be, with ruins of a less determinate description. The theatre faces exactly towards the N. N. E., where it had a closed front, with Doric wings, fan or shell-topped niches, and Doric door-ways, and a range of pilasters above these, marking a second story. There was only one flight or rather division of seats, consisting of seven or eight ranges of benches gradually rising, and receding as they rose, in the manner of all the theatres of antiquity. The upper range was terminated by a fine Doric colonnade running all round the semi-circle, the pillars being about three feet in diameter, supporting a plain entablature. The circuit of the upper range of seats was 230 paces, measured as I walked over it. There were nine flights of cunii or smaller steps intersecting the ranges of seats, like rays from the centre to the circumference of a circle, and these were carefully wrought, the edge of each being finished by a nicely rounded moulding, as well as the edges of the benches intended for the accommodation of the audience. The only entrances for the visitors of this theatre, as far as I could discover, were through arched passages in the semi-circular parts, passing under the benches, and landing at the foot of the range of seats now in sight, corresponding with the ancient vomitories, and about thirty in number. The whole of this noble monument of Roman splendour appeared to me to be in the chastest and best taste, and I never more strongly regretted the necessity which obliged me to content myself with a hasty glance of an interesting subject, than while hurrying almost breathless over its ruins […].

The castle of Bosra appears to be nearly of a circular shape, and is much larger than the castle of Assalt, or that of Adjeloon, both of which, however, in the masonry and appearance of its exterior, it may be said to resemble, the rustic style being used in all. Whatever determination might be made, therefore, as to the age and origin of one, would equally apply to all the others. If this of Bosra be originally Roman, and all the Saracenic parts can be accounted for as subsequent additions or repairs, so also might all the peculiarities of the castles of Assalt and Adjeloon be explain+ ed in the same manner. It is a question highly worthy the close investigation, not only of the antiquary but the historian, and as such may well deserve the attention of any future traveller, who may bring to the task more ample means of observation, and more leisure to record them, than it has been my fate to command. I should not omit to mention, in addition to the striking facts of the Roman theatre in the centre of this fortress, and the guard-house with all the peculiarities of Roman style about it at its entrance, that the bridge leading across the broad and deep ditch by which it is surrounded is constructed over Roman arches, which ought to be decisive, till better evidence be shown of the building, to which this bridge leads, being Roman also; unless it shall appear that the semicircular arch was not confined to Roman architecture, but that the Saracens made as frequent use of that as of their own pointed form, which, to say the least of it, is at present extremely doubtful.

Seetzen (1854), I, p.68. Visite le 14 mai 1805.

Auf der Südwestseite der vormaligen Stadt ist das Schloß befindlich, welches auch grösstentheils eingestürzt ist. In der äußern Mauer sieht man auch eine griechische Inschrift auf einem gelben Steine, die aber zu hoch ist, als daß ich sie lesen könnte. — 72sq. Das Fort ist vorhin sehr bedeutend gewesen. Es ist mit einem trocknen ausgemauerten Graben umgeben, wovon das Mauerwerk aber fast überall eingestürzt ist. Jenseit des Graben sieht man die Reste eines schönen grossen Palais [das Theater], wovon 2 Flügel mit mehreren halben Wandsäulen und etliche Säulen eines Säulenganges stehen. Man sieht daselbst mehrere ausserordentlich grosse Quadersteine in dem Mauerwerk und ein Paar Inschriften Das Fort ist rundlich, und man trifft auch darin mehrere Thüren von schweren Steinen, die steinerne Angeln haben. Inwendig war vorhin ein beträchtlicher runder Platz, an welchem das vorhin erwähnte Prachtgebäude herum gebaut ist. Man sieht viele ganz und halbverschüttete Souterrains. Kurz! es ist wie ein altes teutsches Ritterschloss.

Schumacher (1897), p.146-147. Visite en juillet 1894.

Die Burg liegt im Süden ausserhalb der Festungsmauer. Die Garnison der Citadelle war zur Zeit meines Besuches (Juli 1894) auf die Minimalstärke von 100 Mann reduzirt. Der gebildete, deutsch und französisch redende jäzbäschi (Rittmeister), zugleich zweiter Kommandant der Burg, führte uns in die unterirdischen Gelasse derselben, deren südlicher Theil noch die Rundung, Bogengänge und Sitze des ursprünglichen römischen Theaters zeigt. Ein Theil dieser unterirdischen Räume ist ebenfalls römisch, das Meiste scheint jedoch im 7. Jahrhundert nach der Flucht von den Eijubidensultanen gebaut worden zu sein. An der unterirdischen dschämi' steht die Jahreszahl 620 der Hedschra und der Name des Erbauers selim (?) ibn saläli ad-din el-eijübi. Das Innere dieser Moschee bietet wenig Sehenswerthes; der einst schöne Stuck ist abgefallen, und Moderduft und Ungeziefer herrschen in den zahlreichen, mit Stroh und Dünger angefüllten Gewölben. Ein Gang, dessen Anfang man uns zeigte, soll von einem Gelass in der Nähe der Moschee unterirdisch bis salchad führen. Beim Besuche der Gewölbe habe man Acht auf die Cisternenöffnungen, durch die ein Soldat erst kürzlich verunglückte. Von der südlichen Zinne der Burg gewinnt man einen freien Blick auf das kadä cz-zedi, westlich bis an den teil el-chammän und südlich bis zur Steppe. Im vorderen Theil der Burg führen Treppen zu einer gewölbten Cisterne von gewaltigen Dimensionen hinab, welche von dem grossen, theilweise wiederaufgebauten Wasserbehälter im SO des Dorfes gespeist wird.

Butler (1914), p.295.

Castle. I shall make no attempt to describe in detail this great structure, one of the most interesting of its kind in all Syria. Owing to the fact that it is still a Turkish military post, permission to measure it cannot be obtained on the spot. It would be well worth while for some one to obtain special permission of the Turkish government to make an exhaustive study of this very remarkable military structure of thirteenth-century Islam. The one photograph which I present is intended to illustrate the beauty of the massive redouts built of ancient draughted blocks of stone from the ancient city walls mixed with the drums of ancient columns and banded with inscriptions on white marble. It shows moreover a part of the curved wall of the ancient theatre which formed the core of the fortress. The most satisfactory illustration that I have seen of this Castle is that published by Professor Brünnow. This serves to give some notion of the vast proportions of the structure and of the beauty of the stonework.

|

|

|

|

|

Vue de la Citadelle Source : Laborde (1837) |

Vue de l’accès par le pont Source : Laborde (1837) |

Croquis de la Citadelle en juillet

1894 d’après G. Schumacher Source : Schumacher (1897) |