Khân al-Tujjar (av.848/1444)

Localisation : sur la route 65 à Bet Qeshet Intersection derrière l’arrêt de bus.

Réf :

Buckhardt (1822), p.333

Buckingham (1821), p.456-457

Conder/Kitchener (1881), p.394-396

Gal (1985), p.69-75

Guérin (1880), I, p.381-382

Porter (1889), p.170

Stephan (1937), p.84-85

Thomson (1859), II, p.151-153

Wilson (1881), II, p.57

Historique

Le site est situé sur l’antique Via Maris entre le mer de Galilée/Kinneret et khân al-Lajjan, sur le Darb al-Hawarna qui part du Hauran à l’est pour Acre à l’ouest et sur la route de Damas depuis le khân al-Ahmar à Bet She’an au sud et le khân al-Minya au nord.

Le khân est construit en deux phases : la partie sud avec la grande cour est attribuée au marchand damascain al-Mizza (m.842/1438) et l’extension au nord dûe à l’architecte Sinan Pasha vers 1581. Un fort a également été construit sur la colline en face,[1] les deux phases de construction étant bien délimitées par la maçonnerie. Le khân est complété par un édifice non identifié peut-être un bain (en A) et une citerne (en B) ainsi que deux sources d’eau.

Le khân est de plan rectangulaire (86x93m) avec des bastions circulaires aux angles (ceux au nord-ouest et nord-est sont relativement préservés) et des contreforts quadrangulaires sur un mur d’enceinte perçé de fentes faisant office d’ouvertures. Il comprend deux cours entourées de salles surmontées d’oculi hexagonaux, une douzaine d’entre elles sont encore conservées sur les côtés sud et est. Le mur ouest est démoli et la partie nord, plus tardive, a nécessité la construction d’un nouvel accès dans le même axe que le précédent. Un trou de drainage a été repéré sur un contrefort à l’ouest de l’accès nord. Une salle de prière a été rajoutée à la partie sud du khân par Sinan Pacha.

Le site est visité plusieurs fois après les années 1860 et tous les voyageurs de l’époque mentionnent le site comme marché hebdomadaire pour les habitants de la région (voir plus bas), il gardera sa fonction jusque dans les années 1920.[2]

Aujourd’hui en état de délabrement avancé, le site est laissé à l’abandon.

Epigraphie

Pas

d’inscription.

Biblio complémentaire

Lee/Raso/Hillenbrand

(1992), p.55-94

Sharon

(1997), p.230

Petersen

(2001), n°77

Cytryn-Silvermann (2010), p.144-153

Dalali-Amos (2022), p.37-56

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5/ vue du khân depuis la route au sud-ouest |

6/ vue de l’angle nord-ouest du khân depuis la route |

7/ vue du khân depuis l’ouest |

8/ vue de l’angle nord-ouest du khân depuis l’ouest |

9/ l’angle nord-ouest du khân |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10/ vue du khân depuis l’ouest |

11/ vue du khân depuis l’ouest |

12/ vue de l’angle sud-ouest du khân |

13/ vue du khân depuis le sud |

14/ vue de l’extrémité sud du khân depuis la route |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

15/ vue de l’angle nord-ouest du khân depuis l’ouest

|

16/ la tour nord-ouest depuis l’est |

17/ vue de la façde nord, partie ouest |

18/ vue de la façade nord |

19/ l’accès du khân sur la façade nord |

|

|

|

|

|

|

20/ l’arche d’accès depuis le corridor intérieur |

21/ salle à l’ouest de l’accès depuis l’intérieur |

22/ salle à l’ouest de l’accès |

23/ salle à l’est de l’accès depuis l’intérieur |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

24/ le mur ouest du khân depuis la cour |

25/ vue du mur est du khân depuis la cour |

26/ une salle du côté est de la cour |

27/ vue du mur ouest depuis la cour |

28/ vestiges d’une salle voûtée du mur est |

Documents anciens

Burckhardt (1822), p.333. Visite le 26 juin 1812.

In three hours and a quarter, we arrived at the Khan of Djebel Tor( الان) large ruinous building, inhabited by a few families. On the opposite side of the road is a half ruined fort. A large fair is held here every Monday. Though the Khan is at no great distance from the foot of Mount Tabor, the people could not inform us whether or not the Mount was inhabited at present ; nor were they hospitable enough either to lend or sell us the little provision we might want, should there be no inhabitants. At a quarter of an hour from the Khan is a fine spring, where we found an encampment of Bedouins of the tribe of Szefeyh whose principal riches consist in cows. My guide went astray in the valleys which surround the lower parts of Djebel Tor, and we were nearly three hours, from our departure from the Khan, in reaching the top of the Mount.

Buckingham (1821), p.456-457. Visite le 12 février 1816.

From hence our course inclined a little to the southward of east, until we reached Sook-el-Khan, which we entered an hour before noon. This place is frequented for its weekly bazar on the Monday of the Christians, and, as every description of commodity in use among the people of the country is then collected here for sale, crowds of purchasers are attracted from all quarters. During the six other days of the week, it is entirely deserted, and not a creature remains even to guard the place. There are still existing here the remains of a Saracen fort in good preservation, and a khan or caravansera of the same age, but in a more ruined state : the former of these is of a square form, with circular towers at the angles and in the centre of each wall, and is about a hundred paces in extent on each of its sides. The latter is more extensive, besides having ; other buildings attached to it. Over the door of entrance is an Arabic inscription, and within are arched piazzas, little shops, private rooms, &c., with one good well of water in the centre.

We found assembled on the outside of these buildings, from four to five thousand persons, as well as numerous herds of cattle, Arab horsemen, Bedouins on foot, Fellaheen, or peasantry, from the neighbourhood, women, and even children, were all mingled together in the gay contusion of a European fair. We turned into the Khan to water our horses, and halted for half an hour in the shade, as the heat was oppressive, the thermometer being at 92", and the whole country parched by the long drought.

Guérin (1880), I, p.381-382. Visite en 1863.

A une heure quarante-cinq

minutes, parvenu au bas du Thabor, je prends la direction de l’est-nord-est,

puis du nord-est.

A deux heures quarante-cinq

minutes, j’arrive au Khan et-Toudjar, « khan des marchands ». Ce

caravansérail, qui date, dit-on, de la fin du XVIe siècle, affecte une forme

carrée et mesure 115 pas sur chaque face. Soutenu par des contreforts et

flanqué aux quatre angles d’une tour ronde, il a été construit avec des pierres

blanches de nature calcaire et de moyenne dimension ; mais plusieurs assises

parallèles de pierres noires et basaltiques ont été intercalées tout autour

comme une sorte d’ornement. Au dedans de l’enceinte, on remarque une mosquée et

de grandes galeries voûtées qui tombent en ruine. D’énormes figuiers ont pris

racine dans une cour déserte ; une source y coule.

A 150 pas de là, vers le

nord-ouest, sur un petit plateau plus élevé, se trouve un second khan,

également carré, et qui mesure 88 pas sur chaque face. Le mur d’enceinte est

flanqué aux quatre angles d’une tour percée de meurtrières et qui, circulaire à

l’intérieur, est octogone au dehors. Une tour semblable avait été bâtie

pareillement au milieu de chacun des côtés. Les pierres avec lesquelles le mur

a été construit ainsi que les tours sont blanches, calcaires et grossièrement

taillées en bossage ; elles sont entremêlées d’une espèce de cordon de pierres

basaltiques, dont la couleur noire tranche avec la leur. Au dedans de

l’enceinte, les différents batiments qui la remplissaient ont été rasés de fond

en comble.

Tous les lundis, un marché se

tient en cet endroit, où les Bédouins viennent vendre des bestiaux.

Wilson (1881), II, p.57. Visite en 1864-1865.

To reach the latter from Tiberias, we ascend from the lake a thousand feet, and reach the edge of an uneven table-land, which stretches to the south almost to the very foot of the mountain. This is a region of great fertility, and, toward the western part, is dotted with oak-groves, which adorn the valleys and gentle slopes, and furnish delightful shade. Its broad fields are finely cultivated, and rich harvests reward the husbandmen. It has a few small villages, but the most interesting point is the great khan of merchants. Khan et Tujjdar, called thus from the fact that fairs or markets are held there every Monday. The buildings are not kept in repair, nor is the place inhabited, but on market-days the whole region is alive with tents and camels, horses, donkeys, sheep, goats, and cattle, men, women, and children, peasants, Arabs, and Jews. There is a good deal of noise and loud talking ; the barking of numerous dogs adds to the general confusion ; buying, selling, and exchange go on until the day is ended, and the following morning discloses the fact that the busy crowd has dispersed. Much of the trade is what we call "barter," but Arabs from a distance, and peasants and village-people, are able in this way to supply themselves with what they need for their tents and houses, or for their work in the fields.

Conder/Kitchener (1881), p.394-395. Visite en 1874-1875.

Khan et Tujjar, or Suk el Khan (O i) - This is a fine building of well-dressed stones, in the best style of Arabic masonry. It is now in ruins, and is not used as a khan. It forms one of the line of great khans on the Damascus road, the khan at Beisan and Khan Minia being to the south and north of it respectively. To the north-west of the khan there is a fortress on a slight eminence, in which the inhabitants of the khan could protect themselves from any raid of Arabs. The towers are octagonal, and are built of well-cut stone drafted, and showing a slight rougli boss. The stones are small and of white limestone, 1 foot square, and the masonry is Saracenic in character. The masonry of the khân is not drafted, but is well dressed. The walls are strengthened with buttresses, and the towers are round. The windows are small loopholes. The interior is a mass of ruined arches, with remains of stables at the southern end, and a building containing a spring in the centre.

The Khan measures 360 feet long, by 249 feet wide. The fortress measures 218 feet long to the outside of the towers, and 150 feet wide. The towers are 23 feet in diameter, and the walls are about 5 feet 6 inches thick.

There is a market held at this khan every Thursday.

Porter (1889), p.170. Visite entre 1849 et 1859.

The road from Hattin to Tabor

runs through delightful, park-like scenery. Thin forests of oak clothe the

uplands on each side and the face of Tabor, which rises straight before us with

its graceful rounded top and gently sloping sides. There are here and there

along the path thick clumps of evergreens, holly, myrtle, and prickly oak, with

quiet winding glades between, carpeted with luxuriant grass and spangled with

bright flowers. About half-way from Hattin to Tabor is a large caravansary

called Khan et-Tujjár, " The Merchants Khan. " There are two

buildings ; one a regular khan, or wayside resting-place for caravans and

merchants, with its open court and ranges of little cell-like rooms round it,

and its stables and magazines, and tanks for water, and a mosque. The other

building is fortified like a castle, with loopholed towers at the angles. Both

were erected about three centuries ago by Senan Pasha of Damascus. There is a

series of them extending along the great road from Damascus to Egypt on the one

side, and to Aleppo on the other. I have visited many of them - Khan esh-Shikh,

Sasa, Kuneiterah, Jisr Benat Yakub, Khan Jubb-Yusef, Khan Minyeh, Khan et-Tujjar

; all at about equal distances on the road from Damascus toward Egypt, and all

on the same plan of commodious and secure halting-places for caravans. There

are others on the leading

highways through the country, as

that from Damascus to Hamath on the north, and towards Mecca on the south. From

an Arabic manuscript in my possession I learn that most of them were either

founded or rebuilt by Senan Pasha, an enterprising and patriotic governor of

Damascus in the year 1587. Khan et-Tujjâr is still occupied by a few families of

Arabs, who supply passing travellers with coffee, and with barley for their

horses and mules. But in none of the khans is there furniture of any kind ; and

as a rule the traveller will not find provisions, even the simplest. No regular

charge is made by the keeper, but it is usual to give him a small gratuity on

leaving.

Khan et-Tujjâr is beautifully

situated in a broad, wooded vale with rich pasturage, shade, and shelter-most

grateful luxuries to the weary traveller in this land of sunshine and

exhausting heat. Were it only safe from Arab marauders, it would be a good

centre for pleasant and interesting excursions through the whole of Eastern

Galilee. But it is not safe. The Hawâra nomads are generally found among its

pastures, and they resort to its fountain to water their flocks and herds. They

are given to plunder, and it is scarcely possible for an unprotected wayfarer,

or even a small party, to escape their exactions, or at least their persistent

demands for bakhshish, not unfrequently accompanied

by threats. Within the walls of the khan the traveller is safe ; but the stench of the courtyard, the dirt of the rooms, and the vermin that infest them, are perhaps even more formidable enemies to encounter than predatory Arabs. A great fair is held at the khan every week, and is frequented by villagers and nomads from far and near, who come to buy, sell, and barter. Many of them come to steal, and it is thus a noted gathering place for thieves.

Evliya Celebi, in Stephan (1937), p.84-85. Visite en 1649.

« It is a square, perfect fortress, built of masonry in the midst of a large, verdant meadow. It has a circumference of six hundred paces. The garrison consists of a warden and 150 men. It has a 'double' iron gate facing north. Inside the fortress are between forty and fifty rooms for the garrison. ... Inside the fortress is the Mosque of Sinan Pasha, an artistically constructed work, with a lead roof, full of light. Its windows have light blue glass enamel fixed symmetrically with rock crystal and crystal (?). It measures eighty feet each side. The sanctuary has three graceful and lofty minarets Praise be to the Creator, as if they were three young coquettish muezzins and seven high domes. The wayfarers are lavishly given a loaf of bread and a tallow candle for each person, and a nosebag of barley for each horse, free of charge. On either side of the fortress is a caravanserai with eight shops. »

|

|

|

|

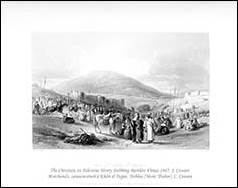

Vue du khân al-Tujjar Source : Stebbing (1847) |

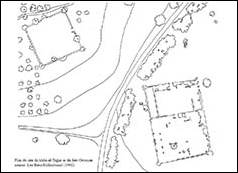

Plan du khân al-Tujjar Source : Conder/Kitchener (1881), p.394 |