Tombeau shaykh Murad (736/1336)

Localisation : dans un cimetière à 2,5km à l’est de la ville, à l’angle des rues Kibbutz Galuyot et Hachmei Lubin.

Réf :

Clermont-Ganneau (1896), II, p.152-154

Conder/Kitchener (1882), p.275-278

Meinecke (1992), 9C/338

Clermont-Ganneau (1896), II, p.154

Kay (1898), p.247

Pedersen (1928)

RCEA 5687

Sharon (2007), p.115-118

Sharon (2017), p.58-62

Sharon/Schrager (2013), p.139-158

TEI, n°7349, 59950

Historique

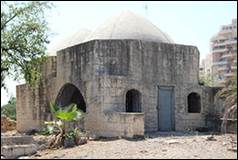

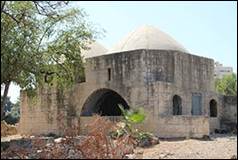

L’édifice renferme la tombe du shaykh Murad, un saint local ; c’est un édifice présentant deux salles couvertes chacune par une coupole. Le bâtiment actuel est une restauration.

En 1949, l’archéologue Jacob Ory[1] revisite le site et en fait la description suivante :

« The maqām contains two chambers. It has a domed roof and a small uncovered yard. One of the chambers contains a tomb and in the other one a recent tomb. The entrance to the maqām is through the yard. The height of the walls is 1,5m. At the western wall next to the corner, inserted into the wall is a slab of marble stone 34×60 cm., bearing an Arabic inscription with four lines. It seems to be an epitaph and it is not the Mamlūk inscription mentioned above ».

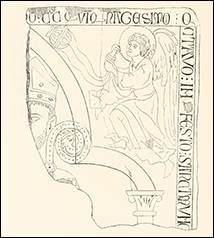

En 1874, une inscription latine mentionnant un évêque mort en 1258 est découverte près du tombeau (ill.8).[2] Le dos du bloc a été réutilisé pour recevoir une inscription de restauration de l’émir Jâmal al-Dîn xxx, datée 736/1335. Cette inscription, appartenant à la collection Ustinow, est conservée au Musée d’Oslo.[3]

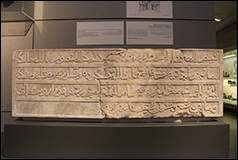

Une autre inscription est retrouvée en 1932, scellée dans la maçonnerie du tombeau[4] ; datée 626/1229 elle mentionne le travail de l’Empereur Frederick II.[5] Ce bloc inscrit est un remploi provenant certainement d’un linteau de porte de la citadelle de Jaffa. Seule une partie de l’inscription a été retrouvée, une partie du texte de l’inscription et une partie reconstituée sont exposés au Musée National (ill.7).

Epigraphie

626/1229. Inscription au nom de l’Empereur Frederick II, 4 lignes (35x56 à l’origine) concernant le mur d’enceinte de la ville, retrouvée enchâssée dans le mur, aujourd’hui au Musée National d’Israël (ill.7).[6]

« [The august Caesar]

Emperor of Rome, Fre[derick, the victorious by (the help of) God, ruler of

Germany and Lombardy, and Calabria and Sicily and the Syrian kingdom of

Jerusalem ; the fortifier of the imam of Rome, the protector of the

Christian community, [in the month of february of the year 1229 of the

incarnation of our lord Jesus Christ… »

736/1336. Texte de construction 7 lignes (37x72) au dos d’un bloc de remploi portant une inscription latine, conservé à la collection Ustinow au Musée d’Oslo.[7]

« Coran IX, 18. (La fondation de) cette

mosquée bénie (a été ordonnée par) xxx l’émir Jamâl al-Dîn xxx à la date de

l’année 736 (1366) ».

Biblio complémentaire

Pringle (1993), p.268-269

Petersen (2001), n°60

Sharon (2007), p.113-119

Sharon/Schrager (2013), p.139-158

Sharon (2017), p.58-62

|

|

|

|

|

|

1/ vue du cimetière |

2/ le tombeau depuis l’est |

3/ le tombeau depuis le nord |

4/ le tombeau depuis l’ouest |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5/ l’intérieur depuis le nord |

6/ les 2 coupoles depuis l’est |

7/ l’inscription au nom de l’Empereur Frederick II

conservée au Musée National d’Israël |

8/ copie de l’inscription latine datée 1258. Au

recto l’inscription de construction datée 736/1336 |

Documents anciens

Clermont-Ganneau (1896), II, p.152-154. Visite entre novembre 1873 et novembre 1874.

Slab from the tomb of a Bishop of the

Crusaders: While exploring the gardens round Jaffa to find the exact position

of the ancient burying-ground, I penetrated as far as the wely of Sheikh Murad,

which lies on the extreme edge of the gardens, in the north-east corner, about

2500 m. from the town. The Sanctuary is guarded by an old Mussulman, who told

me he had found close to the Kubbeh a large inscription and bas-relief. The

object had been removed by someone whose name he did not know. Finally, after much

searching, I discovered that this someone was a converted Jew, and found the

stone in question at his house.

Afterwards, in 1881, I again saw the original in the possession of Baron

Ustinoff, who had acquired it meanwhile from its possessor.

This important fragment, for such it

is, consists of a slab of veined white marble, measuring at the present time

0’’70 by 0’’55, and only 0’’05 in thickness. Even this fragment is broken into

two portions, which fit one another exactly.

Here we see, carved in outline, a

full-face representation of a man with shorn beard, with a mitre on his head,

and holding in his left hand the episcopal crozier. It is hard to say, a

priori, whether this is a bishop or an abbot with crozier and mitre, the rule

as to the position of the crozier on the right or left side being far from

absolute in the Middle Ages. The head and

shoulders are surrounded with a

trilobated arcade resting on a small column with a capital. In the right

portion of the arcade there is represented a winged angel, with a nimbus,

carrying incense, which he wafts round the head of the deceased. This bit is

wonderfully life-like. The whole of the drawing is remarkably bold and decided

and recalls at first sight the 13th century style. Evidently, we have here the

remains of one of those flat tombs, sunk to ground level, that were so numerous

at this period. I am much inclined to think that the slab was not only carved,

but inlaid, as the grooves of the letters have vertical sides, and were

probably destined to be filled with a hard coloured paste. One can further

notice some deep holes on the mitre and the crozier, where enamel and coloured

glass were let in, to imitate precious stones. This slab must have represented

the deceased at full length, but all that is left of it is the left half of the

head as far as the place where the shoulders spring from. The primitive slab

must have been divided into five or six pieces; I shall endeavour presently to

determine the date when this occurred.

All round the figure of the deceased

there ran a Latin inscription in mediaeval letters, forming a kind of border.

This it is possible to restore in part. It commenced apparently at the

left-hand top corner of the slab, then turning downwards it passed along the

right side, the long way of the stone, and continued along the other two sides

till it ended where it started from.

The following is my reading, the parts

that can be restored with certainty being enclosed in brackets:

« [Anno d(omi)ni millesim]o

ducentesimo, qui (n)quagesimo octavo, in festo sanctorum ».

In the year of our Lord one thousand

two hundred and fifty-eight, in the day of the feast of the saints...?

The day mentioned may be, according as

the last letter, which is partly obliterated, is read O or C, either the feast

of All Saints {Sanctorum Omnium), that is to say November 1st, or else

that of Saints Cosme and Damian, that is to say September 27. The date

of the year is beyond doubt, it is 1258. What high functionary of the Church

can this have been? A bishop, or an abbot with crozier and mitre? If a bishop,

was he Bishop of Jaffa, and was there a bishopric of Jaffa at the time of the

Crusades? Does the stone belong to Jaffa itself, or was it, as so often

happens, transported from some other place on the coast? I have elsewhere

entered into a detailed discussion of these different points. They are

difficult to settle with precision, and I am not concerned to recur to them

now—it would take me too far—but some day perhaps I will. There is however one

peculiarity that I cannot refrain from mentioning, the stone is opisthographic.

The back has subseqently been covered with an Arabic inscription, which I will

merely give here in translation:

« In the name of the forgiving

and merciful God. Of a certainty, he builds (or restores) the mosques of God,

who believes in God, and in the day of resurrection, who prays, who gives alms,

and fears God only; it may be that there will be among those that follow the

right road (Koran, Surat IX, verse 18). The building of this blessed mosque

(mesjed) was ordered by the humble Emir and poor before God most High, Jemal ed

Din . . . son of Ishak, on whom may God have mercy. In the year seven hundred

and thirty-six ».

This Arabic inscription is arranged in

such a way on the reverse ot the fragment of gravestone, as to prove that the

original slab was already divided into five or six pieces in the year 736 of

the Hegira, answering to the year 1335-1336 of our era. It was about this date

that a piece of the slab, in shape nearly square, was cut away and the Arabic

inscription engraved on the back. It is most annoying that we have not the full

name of the Emir Jemal ed Din, for this would enable us the more easily to find

mention of him in Arab writers. Then it would appear if he was Emir of Jaffa or

of some other

town on the coast, in which latter

case Jaffa would not have been the first home of the stone of the Crusaders,

and in this roundabout fashion we might perhaps succeed in establishing the

identity of the deceased, who was contemporary with the Crusade of St. Louis.