Citadelle de ‘Amman/Qal’at ‘Amman (n.d.)

Localisation : sur le Jabal al-Qal’at, au nord-ouest du quartier antique.

Réf :

Baedeker (1912), p.143-144

Bennett/Northedge (1977), p.172-180

Conder (1889), p.29-35

Meinecke (1992), 19B/12

Meistermann (1909), p.286-287

Northedge (1977), p.5-14

Zayadine (1977), p.20-57

Historique

La citadelle a conservé de nombreux vestiges de ses différentes périodes d’occupations en majorité Romaine et Omeyyade (ill.21-31).[1]

Parmi ces vestiges, quelques uns sont datés de la période médiévale :

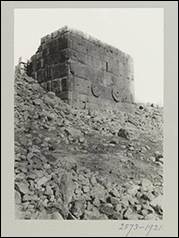

La tour B dite ‘Ayyûbide’ (9,3x7,6m) construite à la fin 12e/deb.13e sur le mur du temenos du Grand Temple avec des blocs de remplois pris aux alentours (ill.12-20). Mal en point au 19e siècle et dépouillée de ces blocs de pierre, la tour a été consolidée et restaurée (matériaux de couleur claire sur les photos).[2]

Des sources mentionnent aussi quelques édifices civils (mosquée, hammam, khân) élevés par l’émir Sarghatmish vers 757/1356 mais sans plus de détails, car aucun vestiges n’est connus.

Epigraphie

Pas

d’inscription.

Biblio complémentaire :

Northedge (1993), p.63-69 ; 105-127

Ostrasz (1997), p.395-403

Almagro (2000)

Anastasio/Botarelli (2015)

Anastasio (2022), p.725-730

|

|

|

|

|

|

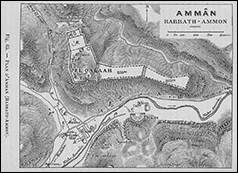

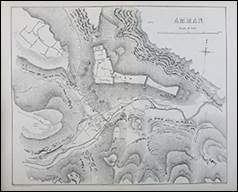

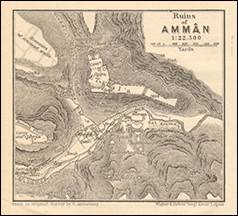

1/ plan du site |

2/ l’angle nord-ouest de la citadelle |

3/ front nord de la citadelle |

4/ l’angle nord-est de la citadelle |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5/ front est de la citadelle |

6/ front est de la citadelle |

7/ front est avec le dôme du complexe palatial |

8/ front est de la citadelle depuis l’est |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9/ vestiges sur le front sud de la cour haute |

10/ le Temple depuis l’est |

11/ vestiges

sur le front sud de la cour haute |

12/ plan de la tour B |

13/ élévations et sections de la tour B |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

14/ élévation est section de la tour B |

15/ sections de la tour B |

16/ la tour B depuis l’est |

17/ la tour B |

18/ façade de la tour B |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

19/ la tour B depuis l’ouest |

20/ la tour B depuis le nord |

21/ le Temple romain depuis l’est |

22/ le Temple romain depuis l’ouest avec la tour B à

droite |

23/ la mosquée omeyyade |

|

|

|

|

|

|

24/ la mosquée et l’accès au complexe palatial |

25/ le complexe palatial depuis le sud-ouest |

26/ vue du complexe palatial vers le nord |

27/ vue du complexe palatial le nord-est |

|

|

|

|

|

|

28/ la citerne à l’est du complexe palatial et la

mosquée |

29/ la citerne |

30/ vue du complexe palatial |

31/ vue de l’église depuis l’ouest |

Documents anciens

Conder (1889), p.29-35. Visite entre août et octobre 1881.

The Kalah, or ' castle,' of 'Amman occupies the long tongue which runs out south and east on the north side of the stream. It is divided from the hill of which it is naturally the continuation by a saddle on the north side of the fortifications, which seems probably to have been artificially cut down. The fortress is L-shaped ; the short line north and south measuring 1,-00 feet, and the long line running east for 2,700 feet.

The western part is the highest, and its surface is about 400 feet above the stream ; the eastern part is divided into two terraces. The irregularities of the plan will be seen by the special Survey, and are due to the conformation of the hill plateau. The western, or upper, terrace of the Kalah includes the remains of a temple on the south, an Arab building near the middle, with a large well east of it, a court of the Roman period further north, and additions of the Arab period. The tower on the south wall, and the gate on the east, as marked on the special Survey, also require a few words.

The exterior rampart walls of the Kalah are standing on all sides, and at the north-west corner their height is from 30 to 40 feet. They are built of drafted stones, averaging about 2 feet in height, and from 2 feet to 4 feet in length. Each course is stepped back from the one beneath about 2 inches. In the north-west angle, where the hill rises very steeply, there are several breaks in the horizontal joint-lines. The masonry may be either Roman or Byzantine, but perhaps more probably the former. The largest stones do not exceed 5 feet in length, or 3 feet at most in height. The masonry is thus in size (and also in finish) inferior to that of the Kalah at Baalbek, or of the Jerusalem and Hebron Harams.

The drop from the western terrace, which measures 1,200 feet north and south, by 600 feet east and west, is about 30 feet. The second terrace, 1,000 feet long east and west, by 300 feet north and south, falls gradually in its length some 50 feet more. The third, or most eastern, terrace, 1,1 00 feet long east and west, and 200 to 300 feet wide, is 30 feet lower on the west, where is a kind of moat 10 paces (25 feet) wide, with a very slight counterscarp, and it is 100 feet lower on the east than the level of the middle terrace at its east end. The whole area of the Kalah plateau is thus 1,295,000 square feet, or about 29 acres, which is less than the area of the Jerusalem Haram (35 acres). The north wall of the eastern, or lowest, terrace is built of rough unshapen blocks of moderate size. It might, perhaps, be older than the ashlar of the western, or highest, terrace ; but it is also possible that it is a mere retaining wall,

and therefore more roughly built.

The court marked towards the north of the highest, or western, terrace appears somewhat to have resembled the great court at Baalbek on a smaller scale. The remains of the north wall, and of parts of the east wall, are clearly of the Roman period. On the north wall the south face is adorned with alcoves about 3 feet in diameter, with a round or haltdome roof which appears to have been ornamented, as at Baalbek, with a scallop-shell pattern. One alcove at the south end of the east wall still remains, showing a little sculptured pediment above its dome. On the north wall seven alcoves are visible, and the remains of two entrances. The masonry is much weathered, but was originally very well cut ; none of the stones are drafted. They are of square proportions, with fine joints. The alcoves were no doubt intended for statues. The court measured 380 feet east and west, and 300 feet north and south.

The eastern gate leads from the higher western terrace to the second terrace on the east. The gateway or porch consisted of three entrances with four pillars. The central entrance was 8 feet wide; the side entrances were 3 feet wide. Each of the four pillars stood on a base 3 feet square, and on the north a little flanking tower, 4 feet from the north side of the north pillar, projected eastwards, and was 27 feet square. This tower is at the corner of the fortress wall, which here recedes west, as will be seen on the special Survey. The bases of the four pillars remain in situ, and are like those of the temple further west on this hill. There are letters or signs incised on the flat surface of the bases where the shaft stood. When the pillars were erect, these signs were of course invisible, and their object is not clear ; but they may be compared with the marks on pillar bases at Ascalon. These signs were also observed by De Saulcy ('Voyage en Terre Sainte '). It seems as if the inscription was originally the same on each base.

The letters are Greek, and the uncial shape of the E and 2 is that used in inscriptions as late as the fifth to the eighth centuries in Palestine. Possibly the letters may have been cut in later Byzantine times by pilgrims or others, after the pillar shafts had fallen.

The great temple was not in the same axis with this gate, but rather further south. Only the foundation of the pronaos or porch remains, and scattered fragments of a huge cornice. The pillars have fallen, and only the bases remain, four on the east and one on the north, and another on the south side of the porch. They stand on a wall 10 feet high, which is 52 feet north and south, by 23 feet 7 inches esat and west. The shafts lying on the ground are 4 ½ feet in diameter ; and battered capitals of the Corinthian order were also lying on the ground. The building must have been a very large one, as the pillars exceed in diameter any others at ‘Amman. On one of the bases again occurs the same inscription above noted on the baese of the eastern gate.

The western part of the temple has so entirely disappeared as to suggest that the building was destroyed by the Christians of the Byzantine period. The cornices or epistylia are 3 ½ feet high, and bear Greek inscriptions. It is extremely difficult however, to read these, and De Saulcy's reading is quite different to that now given. The name Aurelius may perhaps be

distinguished with the words ' of the Gods.'

This temple may be supposed to be that of Hercules, the later representative of the Sun deity, here worshipped by the Ammonites ; for the coins of Philadelpheia bear the name Heracleion. Stephanus of Byzantium calls the city Astarte, and some of the coins bear a figure of Ashtoreth. No doubt, as at Tyre and elsewhere, the male and female deity were both adored.

On the south wall of the Kalah are two towers, as marked on the special Survey. Of these the western is the best preserved, and is a conspicuous object on the hill-top. It is about 30 feet square, and built of drafted masonry. On the north side is the door, which has a flat lintel, and a low relieving arch above the lintel. The relieving arch of five voussoirs has carefully dressed drafts to each stone, and the faces of the bosses are also dressed flat. The lintel has a winged tablet in low relief cut upon it. The whole arrangement and execution resembles that of Byzantine doorways, and this suggests the possibility that the walls of the Kalah are not older than the Christian period (fourth to sixth centuries). The stones in the tower are, however, very carefully dressed, and much better finished than is usual in Byzantine work in Syria. Some are drafted, the draft being 3 inches to 6 inches wide. The corner stones, which are the largest in the walls, are 5 feet long and 3 feet to 3i feet high. The south wall is ornamented by two discs, each 4 feet in diameter, and projecting 6 inches ; these were evidently cut for their present position. The bosses of the drafted stones are carefully dressed with an adze-dressing ; the drafts have a diagonal tooling with a pick.

On the saddle of the hill, outside and immediately north of the Kalah, a very fine rock-cut tank was found by the Survey party. The entrance is on the north, a rock-cut door 4 ½ feet wide, inside which a very steep slope leads down to the floor of the tank. The mouth (see special Survey) is about 50 paces (125 feet) north of the middle tower, in the north wall of the Kalah. The tank is 20 to 30 feet high, and rough steps are cut in the descent from the entrance, and on one side is a kind of shoot with a rock-cut parapet-wall, as though for letting in water. The main part of the tank is 20 feet wide and 93 feet long, north and south. There is a recess on the west with an arch-shaped roof, and the roof of the main chamber is also rounded like a vault. The corresponding recess on the east is 18 feet wide, 25 feet to the back ; and on

this same side there is a third recess of about equal size. In general character this rock- cut hall resembles one at Sheikh Abreik. There is a curious passage just inside the entrance, not far below the level of the rock surface ; it runs in at first eastwards, but gradually curves round southwards. It was pursued for 40 feet, when it becomes choked. It is 4 feet wide at the entrance, but gets gradually narrower and smaller as it goes south. It seemed possible that this was a secret passage from the interior of the Kalah, and may have led to a postern inside the tower above mentioned.

It seems probable that this tank and passage are mentioned by Polybius, who states that, when Antiochus the Great besieged Ptolemy Philopater's forces in B.C. 218 in this citadel, a communication with the external water-supply, by means of an underground passage, enabled the garrison to hold out until it was discovered to Antiochus by a prisoner.

Immediately north of the tank-mouth there is a little shrine or place of prayer with low walls and no roof ; it measured 8 paces (20 feet) north and south, 14 paces (35 feet) east and west. It has a Mihrab in the south wall, and appears to be of no great antiquity.

Meistermann (1909), p.286-287. Visite en 1907.

El Qalaah, la citadelle, est

assise sur un haut plateau en forme d'équerre. La branche la plus longue, qui

mesure environ 900 mètres de longueur sur 80 de largeur, court de l'est à

l'ouest, et la plus courte d'environ 400 mètres de longueur sur 200 de largeur

part de la première, vers l'orient, pour se diriger du sud au nord. La colline

est entourée de tous côtés par des vallées escarpées, excepté au nord où une

échancrure artificielle la sépare du reste de la montagne. Le haut plateau est

formé de trois terrasses qui montent de l'est à l'ouest à une hauteur de 133

mètres au-dessus du cours d'eau. L'enceinte qui l'entoure de tous côtés et qui

a conservé 10 mètres de hauteur, à l'angle nord-ouest, est de construction

gréco-romaine. Parmi les nombreuses tours qui flanquaient le rempart, celle du

sud-ouest attire surtout les regards ; elle mesure 9 m. 25 sur chaque face et

est munie d'une belle porte du côté du nord. A la jonction des deux branches de

l'équerre, s'élevait une porte monumentale à trois baies, dont la centrale

avait 2 m. 50 d'ouverture. Il en reste les bases des 4 piliers au milieu des

débris accumulés à l'entour. Puis vient un grand temple de style corinthien,

dont on ne voit que les soubassements du pronaos, et des morceaux de corniches

et de colonnes mutilées qui ont toutes 1 m. 60 de diamètre. Trois fragments

d'une inscription grecque nous apprennent que ce temple a été bâti sous le

règne de l'empereur Marc-Aurèle (161-180). Il était probablement dédié à

Hercule qui dans la mythologie grecque représentait le dieu-soleil adoré par

les Ammonites. Les monnaies de

Philadelphie frappées à

l'effigie de Marc-Aurèle portent en légende : Philadelphie d'Hercule de Coelé-Syrie.

Baedeker (1912), p.143-144.

La citadelle (el-Kal’a) est située sur la colline N., qui forme un angle au S.-O. et qu’une échancrure (peut-être artificielle) sépare au N. du reste de la hauteur. L’emplacement de la citadelle comprend trois terrasses qui s’élèvent de l’E. à l’O. La porte se trouve du côté sud. Les murs d’enceinte sont épais et construits en gros blocs de pierre sans ciment. Sur la terrasse supérieure (O.) on voit encore les traces d’un temple (les bases des colonnes du pronaos ou vestibule) et une tour bien conservée dans le mur sud. Tandis que tous ces édifices remontent à l’époque romaine, un bâtiment intéressant dit el-Kasr, au N. des ruines du Temple, appartient à l’architecture arabe. Il n’est guère probable que ce fût une mosquée. On admirera la parfaite exécution des détails à l’intérieur. De la citadelle, on a un beau coup d’œil sur l’ensemble des ruines.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Plan de la Citadelle d’après le Survey of Eastern

Palestine Source : Conder (1889) |

Plan de la Citadelle vers 1907 Source : Meistermann (1909) |

Plan de la Citadelle d’après le guide Baedeker Source : Baedeker (1912) |

La tour dite Ayyûbide d’après K.A.C. Creswell vers

1921 Source : collections.vam.co.uk |